By definition, wisdom is specific, local and indigenous.

Therefore, wisdom is native.

And everyone has native skills.

Native skills are located in our prior knowledge, experiences and relational encounters, often embedded in our high points, low points, and turning points.

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, educational psychologist David Ausubel said,

If I had to reduce all of educational psychology to just one principle, I would say this. The most important single factor influencing learning is what the learner already knows. Ascertain this and teach him accordingly. (emphasis mine).

Instead of indoctrinating other people’s theories of human development as the first port of call, why not start with unearthing our own localised theories about how growth and healing takes place, based on our personal experiences?

No matter how well-intentioned, when we begin by swallowing other people's views and approaches, we inadvertently end up mimicking their beliefs, and we become somewhat lazy in trying to think for ourselves, or further shape and mold our own thoughts, informed by our prior knowledge.

This speaks not only how we are trained as psychotherapists, but also how we attempt to help our clients.

Native skills can ferment into native wisdom. Our education, training and development activities can do well to recognise that unlike specialised fields like being a surgeon or a rocket scientist, the craft of psychotherapy does not belong to a “specialised” field of knowledge—the art of conversation is inherent as to our humanity. Conversation is one of the highest art form available to all of us. But to become a good conversationalist, and in our case, for a specific intent of promoting healing and development, needs to be honed in.

Skills and Gifts

In other words, we must be faithful to the gifts of our nature. A colleague of mine is extremely witty without even trying, and he would do well to incorporate his pithy speech, when it serves the client at the right moment, into his therapeutic work.

Another therapist I know has this ability to draw out a visual map in a matter of seconds to have make an abstract idea concrete. Why not use this in therapy?

A third therapist I know, even without all the doctoral degrees and alphabet soup after her name, has the ability to melt your heart and make you want to open up your deepest darkest secrets to her in the first five minutes.

Finally, a fourth therapist I met at a workshop was visibly a metal-head, non-conformist personality. Instead of lining up his clients to be baptised by the CBT manual, he would do well—when needed—to help shine a light with his clients on aspects that are left unchallenged, opening up possibilities of different ways of being that may help clients not be captured by the middle-bum of the bell-curve.

I would argue that many gifts are honed outside of your education in psychotherapy.

Not convinced? In one prospective study, the researchers found that a trainee’s interpersonal abilities influenced results. However, it was their ability measured PRIOR to receiving any training, that predicted actual client outcomes. The 2 years of doctoral training had no significant effect.1

I talked about 3 other studies regarding a similar point on the lack of training effects, and the pressing issues faced in our educational and training programs. See the following piece:

Frontiers Friday #149. Become a Guiding Light as a Clinical Supervisor

What are the most pressing problems in the practice of psychotherapy?

So why not bring what you already have, into the service of your client?

When I first started off, in a systemic family therapy class, the facilitator asked about what I spent my time obsessing with, outside of the professional field. I said music. I played in a band, and loved everything about music. She listened intently to my meanderings on music for a bit, and then she asked me the following question:

"How do you incorporate what you know about music into therapy?"

It’s hard to describe to you the impact of that deceptively simple question. My head was on-fire. I'm not sure why, up until that point, I had not considered cross-pollination.

Some 20 years later, music remains as one of my "root metaphors." As an example, see this essay:

How to Invite Your Native Wisdom

Complete the following sentence,

"When I am at my best, I am like a ____________. "

Resist the temptation to censor yourself. See what metaphor arises from your unconscious.

Here’s mine: “When I am at my best… I am like a complimentary musician in your band, making what you already have, trying to make the song just a little better.”

What’s yours?

Tapping into each therapist’s native wisdom, is a form of alchemy that is required in our field. I say we begin with that, and join the dots to various theoretical frameworks that we learn in therapy school, after the fact.

We build on what we have, like LEGOs.

SEE RELATED:

The second way to tap into your own native wisdom is explicate your own guiding principles:

As to methods, there may be a million and then some, but principles are few. The (person) who grasps principles can successfully select his own methods. The (person) who tries methods, ignoring principles, is sure to have trouble.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essayist and Poet

Your first principles are not your theories.

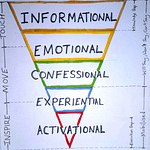

First principles are foundational axioms or basic building blocks that can’t be broken down further, while theories are frameworks or explanations developed to understand phenomena based on available data and observations.

First principles serve as starting points for reasoning, whereas theories are built upon these principles (and other observations) to explain more complex ideas. In other words, you start with your principles, and you explain with theories after the fact. This distinction makes first principles more fundamental and universally applicable, while your theories can evolve and be modified over time. Still, your principles can sharpen over time.

Exercise:

Take a piece of paper. Put on a 15min timer. And list down what you consider your own guiding principles. You might be stumped. Press on. Review your case notes to jolt you a little if it helps.

Once the timer is up, stop. Keep that piece of paper (or digital note). Sleep on it. Make a promise to yourself to come back to it in a week (i.e., put it into your calendar).

Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them… well, I have others.

— Groucho Marx

What’s one of my first principles? I’m trashing out a small book on this topic at the sidelines, so tell me at the comments below if you are interested in such a thing. As you would imagine after reading this piece, one of them is a belief in each person’s native wisdom. And if you have read The First Kiss, you would have picked up another one that guides me in clinical practice: follow the pain AND follow the spark.

For more on the topic of first principles, see these posts:

Client’s Native Wisdom

This brings us to another parallel aspect of native wisdom. Our client’s native wisdom.

I know most of you would say that I already do that, i.e., tap into client’s strengths, etc.

But listen very carefully to the metaphors that you use in your therapy conversation. As we try to help our clients, is our first port of call one of their native wisdom, or one coming from your theories? We might not mean to, but if we fail to build on what client’s already have, the unintended consequence is that we colonise them with our best intentions, rendering them having difficulties hearing themselves clearly. We hear ourselves best when someone listens to us into speech.

This doesn’t exactly show up as a problem at first. Because it might even make sense for that particular client. However, I would argue that we are not therapy missionaries, getting our clients on-board with the schema therapy framework, mindfulness-based, trauma-informed bandwagon. We are more like gardeners.2 We are there to nurture what is already in their nature.

We are to nurture their nature, not impose on their nature.

You see this imposition on ways of thinking proliferating on social media, amping the ever-increasing medicalised ways of thinking about mental health concerns, especially about ADHD, ASD, etc.

I like the argument that I’ve heard several autistic people make, that they prefer to be called autistic individuals and not individuals with autism. The latter suggests that this is part of who they are, and the former implies they are dealing with a dysfunction i.e., something wrong with them. Influenced by my training in narrative therapy, I used to think that this wasn’t a good way to think about it, as I would rather say “a person with autism.” However, framing it as part of one’s personality allows one to see it not as a flaw, but a trait.3

Someone wise once said, it is not a measure of health to be well-adjusted to a sick society.

Our role is to help others align with their souls, so that they have a fighting chance to come fully alive in this one life that we have.

The Tension

This leaves us with another issue.

A therapist brought this up to me: “I attended a training, and I was asked to explain what therapy model I was using, but I wasn’t exactly thinking of a specific modality during the session. I was just doing what I know best at that give moment with that particular client.”

I bet my money that the giants in our field, like Aaron Beck, Carl Rogers, Milton Erickson, Virginia Satir developed their theories, retrospectively.

I don’t think it’s wrong to be able to say from the outset that “I’m doing emotion-focused work, or psychodynamic interpretation.” I just think that there is another way to be with our clients, in a more integral, creative and grounded way of being that is informed by who you are. Where two minds meet. As equals. Exchanging and improvising ideas that catalyses growth.

A therapist is not a bot dispensing manualised treatments to each person that walks into their office—AIs can do this. If generative AI is a threat to our jobs, maybe it’s time to think if it’s because we are behaving more and more like homogeneous robots.

SEE RELATED:

Can ChatGPT Replace Psychotherapy?

Before ChatGPT took the world by storm a few months ago in Nov 2022, there was ELIZA.

Kindle the Flame

The antidote for our sanity and soul is to gravitate towards the dialogical discoveries that occurs when two people or more truly meet each other. From the emergence of logos to dialogos.

We stand a fighting chance to tap into our client’s native wisdom if we do the same for ourselves. From the experience of true conversation, connection, improvisation, creative energy and love, then we will discover fire for the second time in history.

Thanks for reading Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Notice Board

We have only 1 seat left for the Deliberate Practice, DP Cafe group.

This is not a webinar. This is a close-knit collective.

Join Scott Miller and I for four intimate sessions of small group meetings, each organised around your questions and goals with instruction and coaching provided by the group.

For more details and dates, see here.

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, and the latest book The Field Guide to Better Results. Plus, the forthcoming new book, Crossing Between Worlds.

Anderson, T., Crowley, M. E. J., Himawan, L., Holmberg, J. K., & Uhlin, B. D. (2015). Therapist facilitative interpersonal skills and training status: A randomized clinical trial on alliance and outcome. Psychotherapy Research, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1049671

Or plumbers. Take your pick of metaphors to ascribe what you do.

Granted, not everyone prefers identity first descriptions. There are individual differences in preference.