The Music of Psychotherapy: Learning in a Wicked Environment

Updates by Daryl Chow, MA, Ph.D.(Psych)

View this email in your browser

The Music of Psychotherapy: Learning in a Wicked Environment

By Daryl Chow, MA, PhD on Aug 26, 2019 11:47 am

I often get a bewildered look when I tell people that the first place I visited in US was Kansas City. It was also the first time I met K. Anders Ericsson.

In 2010, I was in Kansas to attend the first Achieving Clinical Excellence (ACE) conference[1]. I was excited about this prospect, as it was the first time practitioners from all over the world, who were interested in not only measuring their outcomes, but also figuring out a way to improve our work, was coming together.

It was also the first time I get to meet my mentor and collaborator Scott Miller in person, as we had been corresponding for some time. It was momentous, as I had been a huge fan of Miller’s and colleagues work since 2003 as an undergraduate. I stumbled upon their books like Impossible Cases and Escape from Babel in the school’s dingy library.

Just before the ACE conference, I had just left my full-time position in a mental health institute in Singapore, to do a PhD investigating the development of “supershrinks” in Australia.

Ericsson is a towering giant in the field of expertise. He has been forerunner on the topic of deliberate practice, which was the main theme of my dissertation. (update: For more about the ongoing debate about the contribution of deliberate practice and innate talent, see our most recent re-analysis of a well-known meta-analysis). Listening to his keynote amplified all that I’ve read about the field of expert performance. And I’m not exaggerating, it was a spiritual moment for me. It struck me that the pursuit of excellence was akin to a devotional spiritual practice, of seeing what our deepest potential was, and helping others reach that place within.

Beyond Classical

In speaking with Ericsson, I asked him about why he thought much of the literature on music and expert performance was on classical and not other forms of music, like pop, rock, folk, or even a closer cousin like jazz. We spoke at length about this, touching on issues regarding the lack of reliable measure of performance, the inherit cultural basis of music preferences, and Top 40 music charts not being a reliable source of expertise, and so on. The last thing he said to me about this was, “If you found a way to reliably measure this in other types of music, let me know.”

Nearly a decade’s past, and I’m still pondering about this.[2]

I believe there are are a few things I’m discovering about music that is relevant to psychotherapy.

#1. It’s relatively easier to improve at an instrument, than it is to get better at songwriting.

Much of my teenage and early adulthood years were spent in the world of music. I loved music; it saved me from going south in my life. I played in a band, wrote songs, hung out at music studios, recorded stuff, formally dabbled with the Indian instrument sitar for a few years after being enthralled by the likes of George Harrison and Ravi Shankar (turns out that I had to learn to sit properly for the first few months before I could actually play).

I wasn’t the best guitar player, but I accelerated my skills pretty quickly by devoting 4-10 hours a day, trying to master the licks of Jimi Hendrix, Metallica, Led Zeppelin, Pearl Jam… you name it.

A couple of my older school mates and I formed a band when I was about 14. When we started, I could barely play 3 chords. But that will do. We wrote our very first song with 4 chords. (What ensued was a deep friendship).

As years passed, it started to creep in that that getting good at my instrument was not necessarily making me a better songwriter. Implicitly speaking, there was a sort of unspoken rule that you do not read up on how to be a better songwriter, because if you do, God forbid, you’d lose “authenticity” in your songwriting craft, and become formulaic and “sold out.” I became a frustrated songwriter, waiting for the Muse to knock on my door, while I secretly trying to disentangle rules, principles and rules of thumb in the craft, by incessantly figuring out chord progressions from the The Beatles.

Kind vs Wicked Environments

It turns out that, trying to get good at an instrument, is what researchers Robin Hogarth calls a learning in a Kind Environment.[3] Kind environments are when the feedback loop for the target of learning and the impact of performance are clear. Other examples of kind environments include golf, chess, bowling, and school homework.

On the other hand, a “Wicked Environment” is where the rules of the context are often unclear, and the feedback loop for the target of learning and the impact on the performances are delayed, inaccurate, or both. Examples of wicked environments include poker, soccer, medicine, and life.

While learning an instrument is likely to fall under a kind learning environment i.e., feedback about how well your violin recital is known immediately based on a panel of expert evaluators, I would argue that songwriting exists more on the spectrum of a wicked learning environment.

Does the practice of psychotherapy fall under more or a kind or wicked environment?

I reckon most of us would see psychotherapy more in the spectrum of a wicked environment. That’s because there are so many factors are at play when you meet a client, shifting focus and differing client preferences and idiosyncratic philosophies of what makes a good life. Even if you employ a routine practice of systematically monitoring outcomes, the earliest you’d get feedback about the session is about a week later. Given that psychotherapy exists in a wicked environment, it is not like you could make some pre-determination of treatment on the basis of diagnosis.

It seems to me that our efforts at improving our craft in therapy looks a little like Wicked Environments #3. Worse, some times it looks like Wicked Environment #4, where our learning targets have nothing to do with improving client outcomes. Take for example, the amount of time we invest in theorising the psychopathology of a given psychiatric diagnosis, one step removed from a given client’s worldview, his theories about why he is unwell. In a sense, our well-meaning attempts in applying “evidenced-based” practices (more accurately, it should be called empirically supported therapies, ESTs), is somewhat like the colonisation of a country, thinking we can wholesale import our beliefs onto another, while relegating their existing culture and preferences.

#2. Foundations of music and talk therapy

The second parallel I see in music and in psychotherapy is the importance of understanding the foundations.

In contemporary music, these are four elements that song craft rests upon:

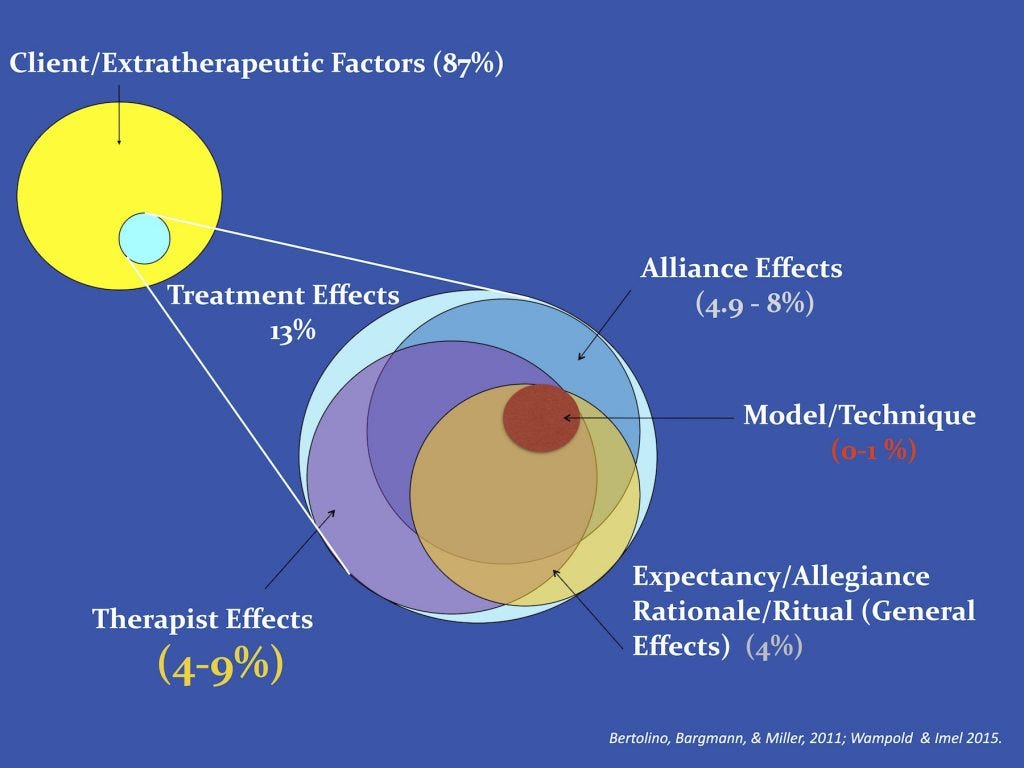

In psychotherapy, we can turn to the composition of research in the outcomes literature done by people like Bruce Wampold and colleagues. See below for the therapeutic factors accounting for outcomes:

Knowing these foundations both in music and in therapy, does not spontaneously make you a better musician or a therapist. But, a good melody does not exist without the bedrock of rhythm, bass and harmony[4]. Likewise, specific techniques in therapy can only shine in the context of a healing context, rationale, structure and alliance, while utilising what client’s bring to the table, in terms of their worldview, personal agency and resources.

The point is, whatever genre of music or types of modality in therapy one is to employ, these factors stand the test of time.

The real question for you and me then, is how does one design for learning in a wicked environment like the practice of psychotherapy?

Design for Learning in a Wicked Environment

Given the above, my hope is that as a field, we can reshape our efforts to approximate what might look like Wicked Environment #5 (see below)

While our learning focus may never entirely look like #1 and #2—simply because psychotherapy does not operate in a kind environment—I believe we can optimise our learning efforts that is more likely to overlap our intended targets of improving client outcomes. Note that the size of the Learning circle is smaller than the Target circle. It’s unrealistic to expect that we have infinite amount of time to absorb information. It’s also non-static. We should strive to approximate our learning efforts towards better leverage of influencing client outcomes. What we can expect of ourselves is to learn to extrapolate and generalise our learnings from all kinds of sources (e.g., books, movies, conversations), and then making the effort to apply that to the therapy room.

Weekly Therapy Learning Logs:

For instance, in one of my weekly therapy learning log (for more about this, see Develop Your Own Wealth of Learnings), I recently noted in note “#265. Visual Arrows, Up, Down; Left, Right.” This was something that hit me in mid-session working with a client that I had seen for more than 8 sessions. I was asking myself, “Should I ‘go up,’ or should I ‘go down’? In other words, I was thinking if we should I go up the ladder of abstraction (e.g., “We need to challenge the default discourse of masculinity…” which i didn’t say), or should I ‘go down’ by moving in deeper (e.g. “What was that like for you receiving the message from Dad?” which I ended up asking him. Turns out that this resonated with him as a therapeutic task to work through).

As I looked back, since writing that note, I found myself having almost a visual hallucination of arrows blip-flashing beside a client, when I’m contemplating which direction to take (I haven’t mentioned that “Left, Right” meant to me to explore further the relational landscape of connections).

More importantly, I suspect this personal learning of the visual arrows came to me because I had been exploring the effects of visual learning and doodling, reading stuff like Visual Meetings, The Back of a Napkin, and the Doodle Revolution). This was my way of extrapolating and generalising learnings from other fields.

Leverage Your Targeted Learnings to Impact on Client Outcomes

If you were to take the framework of Wicked Learning Environment #5 seriously, here are 5 key factors to ensure your targeted learning has leverage on improving your outcomes:

1. Monitor your outcomes

Worldwide, more and more therapists are not only employing a routine outcomes monitoring perspective (ROM) in their clinical work, but are actively using the feedback that they obtain in real-time to feed-forward the treatment process (for more reads on Feedback Informed practices, see the archives).

If you use outcomes on a “one client at time” level, you’d see the payoff when you get to figure out your baselines effectiveness on “therapist level.” This is where things come alive. You no longer need to solely rely on the evidence of empirical studies, but you get to figure out and demonstrate your own evidence of effectiveness. (See In Search for a Personalised Professional Development)

For more, read one of our peer-review publications, like Beyond Measures, or FIT: Achiving Clinical Excellence One Person at a Time.)

2. Figure out “what” to work on before the “how”

Our field is obsessed with inundating therapists (and clients) on the “how” to get better. We somehow underestimate the important of learning that each individual’s “what” to work on is unique. Plus, compared to a kind learning environment (recall: like learning an instrument), taking the time to figure out the “what” is even more critical in a wicked environment, where it is often unclear which areas to work on, amongst the many aspects to focus on.

Once you figure out your baseline effectiveness (see #1), your data can provide you the guidance to develop key questions on what to work, that has leverage on improving outcomes. We have also developed a Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice Activities (TDPA, Chow & Miller, 2015) to guide therapists and supervisors in this process. (More on this in our upcoming book, Better Results).

3. Examine the impact of your learning efforts

Nothing is as depressing as to find out that your learning efforts yield no dividends.

As you establish your baseline (see #1), and work on the specific areas which is at your growth edge (see #2), investigate if your efforts translate to better outcomes. If so, explicate a hunch on why and how this has had on your performance as a therapist.

If the impact of your efforts did not improve your results, ask yourself why hasn’t your efforts translated to better results? Were you working on stuff that does not have a high yield on improving the wellbeing of people that you are helping? Zoom out and consider the therapeutic factors that are known to have leverage on impacting outcomes.

In addition, do you need to get consultation from someone to guide you in your deliberate practice efforts? (See this article, Here’s the Payoff).

4. Keep a weekly therapy learning log

As I’ve already emphasised, I highly recommend you keep a weekly therapy learning log. This highly individualised learning process is particularly useful in a wicked environment like the practise (verb) of psychotherapy.

Bake this into your weekly routine. Take no more than 5 mins, and constraint the number of words to about a hundred.

For more on this topic, see A Memorial Practice, Development Your Own Wealth of Learnings.

5. Retrieval Practice

I have been formally capturing my weekly therapy learnings since 2012. At this point, I have 269 individualised learning.

This is where it gets interesting.

Whenever I look back at my entries, I test myself by looking at only the headers. I’m often surprised that I don’t recall what it was about. In fact, just last week, I noticed that my entry “#269. Give space to open up the conversation”(23 Aug’19), was strikingly similar to entry #40. Trust the process by opening up the space…even when in doubt” (27 Sept’13).

I now make sure I look back at my previous learnings every week (which now also includes mistakes). In the cognitive science of learning, cutting edge research consistently points towards the importance of retrieval practice. The act of actively counteracting the forget curve, increases the depth and retention of learning.

If we are to talk about how we are performing as therapists, we have to talk about how we are learning. In a wicked learning environment like songwriting and psychotherapy, the key here is not to develop a formula for success, but to cultivate a form that supports the development of therapists, so that clients reap the benefit.

Footnotes:

[1] We have had three ACE conferences. I’d admit it, this is the only conference I’ve attended at every gathering.

[2] My original question about music has somewhat evolved. I’m now thinking more about the difference between “The Rolling Stones” vs “David Bowie” effect. In other words, I think I would be worth investigating on what pushes music artists to move beyond their comfort zones, and instead, constantly challenging their own status quo. Yet at the same time, not over tipping what people are familiar with. I believe Radiohead is a good example of this. If you are a fan of Radiohead, read Everything In Its Right Place: Analyzing Radiohead.

[3] Hogarth, R. M. (2001). Educating intuition. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

[4] Some would argue that certain genres of music does not have melodies, like drum and bass. In dance music, it seems that bass overtakes rhythmic values, and even the role of melody. In addition, it seems not obvious at first, but Bass, plays a prominent role in music since four centuries ago, and became more dominant due to Waltz. For more, check out the documentary, How Music Works.

The post The Music of Psychotherapy: Learning in a Wicked Environment appeared first on Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development.

Recent Articles:

6 Visuals About Our Progress

How Do You Go Faster on a Bicycle?

Feathers and Wings, and How We Fly

“Is the Scientific Paper a Fraud?”

To Specialise or Not to Specialise?