Finally.

My colleagues and I can report that this study Improving Responses to Challenging Scenarios in Therapy is now published.

What took us so long?

What can we learn from this study? What are the direct implications for you?

I’d explain a little down below, and I’d tell you what I’ve learned from the DCT project.

If you want to cut to the chase, read the paper yourself. It’s open access (there’s a strange little fact to open access which I naively didn’t know about previously. More on that later).

If you want to listen in on a conversation Scott Miller and I had on this study, watch this video on Scott’s Top Performance youtube channel:

If you are curious about the video vignettes that was used for this study, you can check them out here:

What follows is me trying to break this down, give a little context, and my personal takeaways from this project:

Main findings

Surprising findings

Uniqueness

The Evolution of the DCT Study

What I’ve learned from the DCT Project.

1. Main Findings

In a sentence, therapists who participated in this study significantly improved their ability to handle difficult conversations with clients.

In this experimental design of a deliberate practice protocol, participants were randomised into a control and feedback group. All participants watched a series of challenging scenarios in this randomised controlled trial (RCT). The control group were not given any feedback and were told to reflect and improve their responses throughout the eight trials. The feedback group were provided individualised, principle-based feedback (i.e., not what to say). They were encouraged to formulate their responses in their own style and voice.

No surprise that on average, participants in the DP group improved.

What was striking is that no change was observed among the participants in the control condition. The control group showed no significant improvement between any of the trials.

2. Surprising Findings

Part of the fun of any study is to have unexpected findings.

Here’s three:

Transfer of learning

“Transfer” of learning is seen as the holy grail in the education and learning sciences literature. Although transfer of learning is universally recognised as fundamental to all learning, yet the current evidence suggest that it seldom happens in instructional settings.

With regards to the lack of transfer in learning, Robert Haskell says“…without exaggeration, (there is) an education scandal.” 1

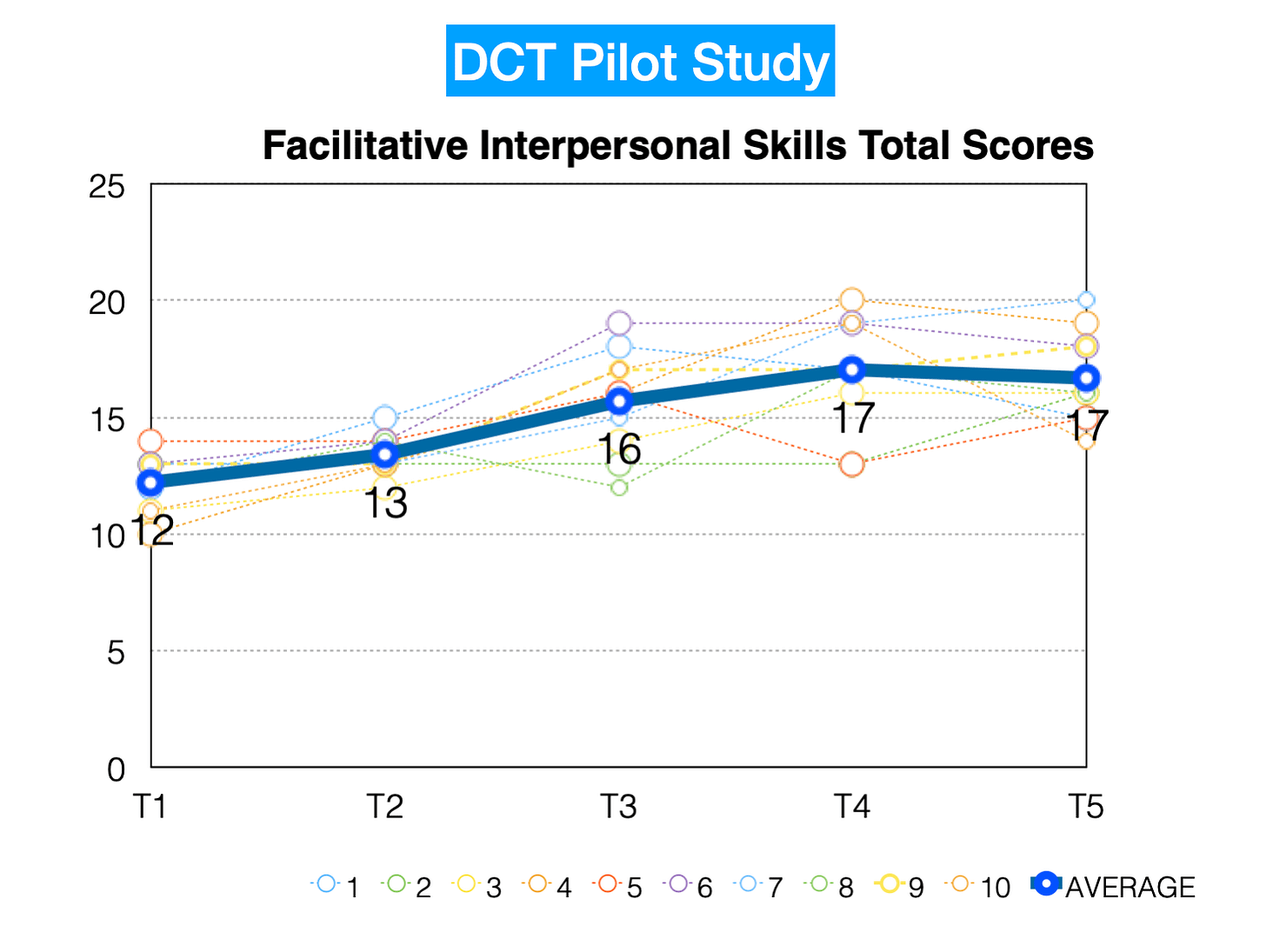

Have another look at the graph. Pay attention to Trials 4, 5, and 8.

For instance, participants were given a “hopelessness” clinical vignette to watch in trial 1. In T2 and T3, they watched the same vignette, and did their best to respond.

In T4, a different client was presented, but still a “hopelessness” scenario.

In T5, however, an entirely different theme was provided (e.g., reluctant client). Participants then repeated this scenario in T6 and T7, and then, just to mess things around, in T8, we provided a similar theme of “reluctant client,” but a different client.

This is where it got interesting. For the DP group (blue line), they not only maintained their abilities (see T3 to T4), but they were also able to transfer learning into an entirely different clinical presentation! (see T4 to T5).

RELATED: See this post on transfer of learning.Self-Ratings

We also got participants to rate their experience of Difficulty and Performance in each step of the way.

Here’s what we found:

- There was no significant correlations between their performance and self-ratings of difficulty (r = 0.065, p = 0.64) and performance (r = 0.145, p = 0.28).- At trial 5, participants in the DP group rated the task significantly more difficult (t(41) = -2.14, p = 0.04).

- Even though they improved in their responses in T2, Self-rated performance of the DP group was significantly worse than controls in T2 (t(52) = 2.42, p = 0.02). Note: T2 is where the first time constructive feedback was provided.Attrition Rates

I initially predicted that the feedback group would have lesser dropouts from the study. However, it was the opposite.

On hindsight, this makes sense. It was challenging to be continuously pushed towards your growth edge each step of the way. The control group weren’t challenged in the same way; they engaged in self-reflection only.

3. Uniqueness

This is perhaps the first study that does not include a “captive audience” of graduate students or workshop attendees. In our sample, 72 practicing therapists from all over the world devoting their own time, over the course of two weeks to the study protocol. The average number of years in clinical practice was 11.6 years (SD: 9.37).

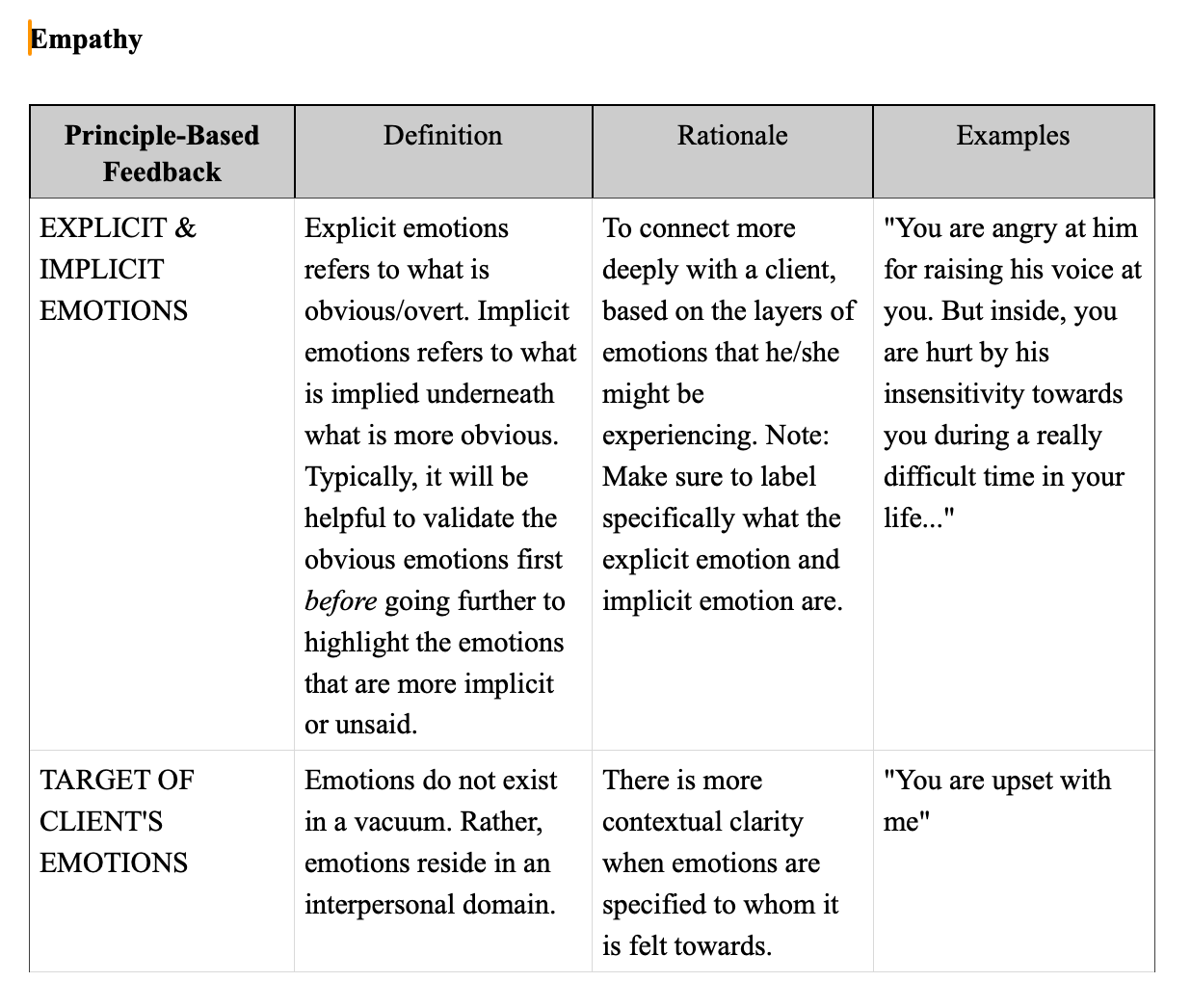

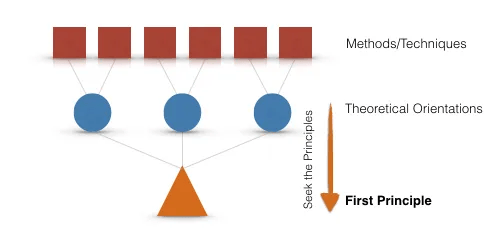

Second, instead of providing formulaic or template responses, participants were provided principle-based feedback. By focusing on principles rather than specific methods or techniques, this allowed participants the manoeuvrability to not only apply their own style, but also generalise this into other related contexts.

Here is an example:

For more on the types of principle-based feedback we employed, see the supplementary materials, Appendix 3.

Next, perhaps logically seen as a limitation of our study, participants provided written responses to each of the scenarios, not verbal responses.

As many of our peer-reviewers pointed out, they saw this as a significant constrain. I think that potentially, it isn’t.

Why?

I would argue that the writing down your responses long-hand, forces you to slow down and think about what you are actually saying. In addition, providing on-the-spot verbal responses might tip the learner into a “performing” mode, instead of staying in their zone of proximal development. This is speculation on my part, and it might be worth testing this out in the future.

(Note: In our pilot study with 10 participants, we have therapists verbally respond while we transcript their words).

4. The Evolution of the DCT Study

This is more of a backstory.

This idea was seeded when Scott Miller and I first met K. Anders Ericsson in 2010. Ericsson gave the keynote address. One of the things he said in passing about other professional domains was the idea of developing an archive of various scenarios, so that people could learn from them.

I was transfixed with the idea.

Not only this sort of archive didn’t exist in our field, but as a clinician, this sort of high acuity low occurrence (HALO) events were rarely practiced.

I would benefit from this too.

We have the content knowledge about these sort of psychotherapeutic HALO events, but not actually the process and conditional knowledge on how to actually address them in conversation.

SEE RELATED:

A few years since that initial idea, Sharon Lu and I formalised the study Difficult Conversations in Therapy (DCT) idea, lodged an IRB to conduct a pilot study in the hospital institution that we were working in. We had ten clinicians who volunteered for the study. They responded to a single challenging vignette based off an actual clinical scenario (e.g., we call it “Angry Annie”), and got one of our colleagues who had acting skills to help us out.

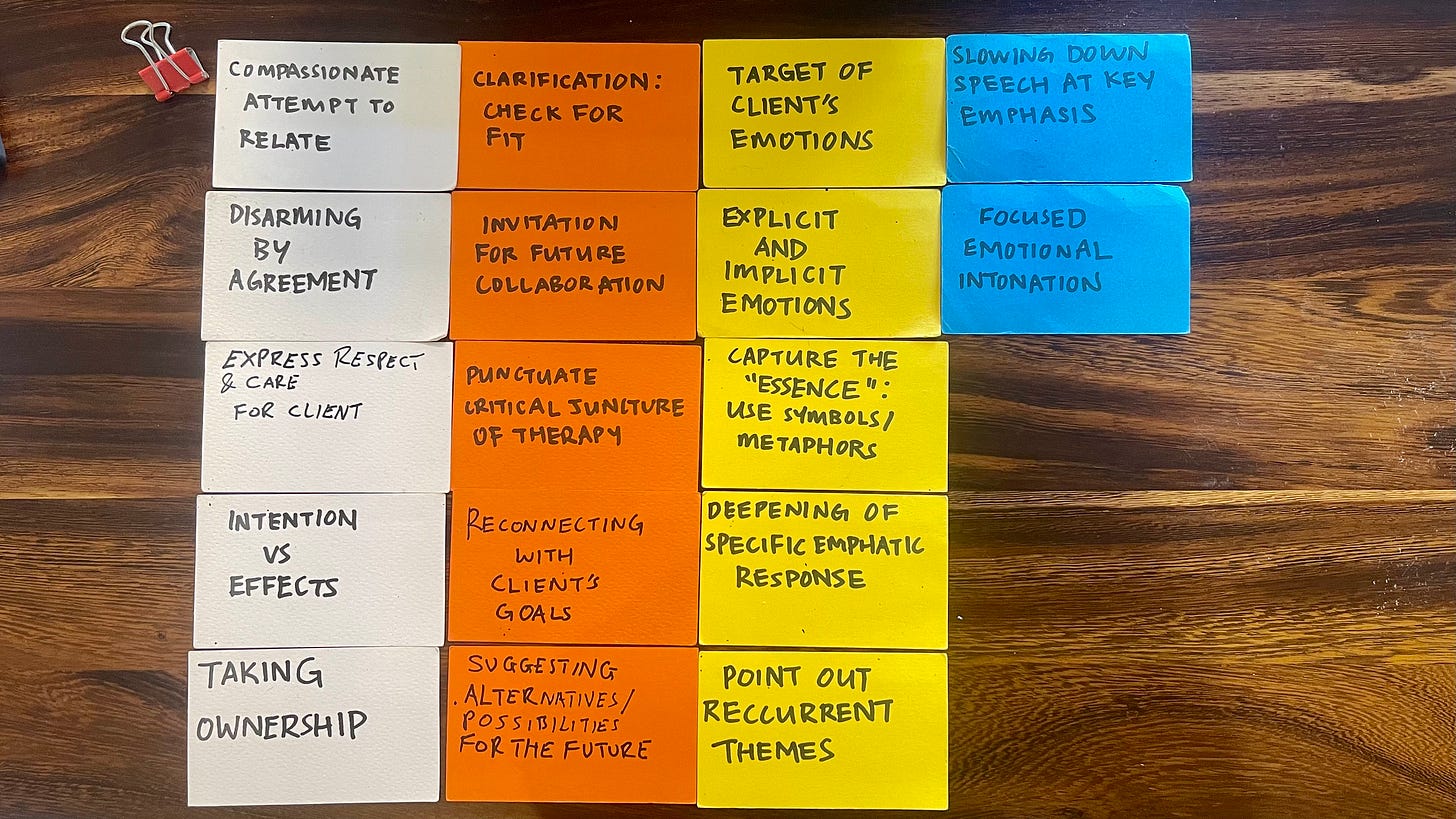

We transcribed every single of the 50 responses in real-time. Before long, Sharon and I noticed that there was a recurrent pattern about the way participants responded to the DCTs, and thought that it would make more sense to provide a “chunked” feedback, based as far as possible on principles, agnostic to treatment modalities.

Here are the original cue cards that we butchered around with:

In a heated situation, we soon realised that therapists had difficulty responding with “disarming by agreement,” addressing the “explicit before the implicit emotions”, and explicating the “target of client’s emotions.” (more about these in the Supplementary materials).

And even though the simulation was artificial, some clinicians had a visceral reaction to the videos. We pondered if the IRB clearance still stands.

In any case, here were the results of the pilot study:

As you can see, we were hopeful with this initial study. We gained some traction, other researchers joined us for the follow-up study, and we began enlisting clinicians internationally.

Time passed. We got audited. Loads of paperwork to file. We got the clearance. I left my job in Singapore. We did the write up. More stats gurus like US psychologist Adam Jones and psychiatrist Geoffrey Tan came on board to help us out with the analysis.

Meanwhile, Geoffrey and Sharon got married (Yay!!). Babies were born. Masters got completed (Yay Tammie Kwek!)…

Given that I was not an academic in an academic setting, I still really wanted to see it through and get this study published. And believe me, we have been trying since 2018.

Frankly, besides our slowness in completing the manuscript, I’m really not sure why we were knocked back several times. One journal held on to our submission for several months and later said that they didn’t have any relevant peer reviewers for our study. For others, many of the feedback were constructive. We kept doing our best to address each reviewers’ concerns, made modifications based on the feedback, and yet failed to pass through the process.

But this time, I thought out loud with my collaborators, that it’s so silly to invest so much time to get this published, and yet, very few people would read the study, given that it would be behind some paywall, unless you are an Academic.

Why should funded studies be behind paywalls? Shouldn’t everyone be allowed to read any study if they choose to?

SEE RELATED:

So we agreed. Let’s publish it in a journal that would be open access.

Geoffrey said to me, “Sure. It will cost us a few thousand dollars.”

What?!

I had no idea that researchers had to pay a range between $1500-$3000 per paper for it to be open access.

How naive of me.

Thankfully, Geoffrey and Sharon could secure funds from the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) to get the article to freely accessed for anyone interested to read it.

6. What I’ve Learned from the DCT Project

Finally, I thought it might useful to share with you my takeaways and discoveries from working on this project:

Who benefited the most from this study?

I think Sharon and I did. We analysed hundreds of responses. We couldn’t help ourselves but also vicariously learn from other clinicians as work towards each of their learning edge.Self-reflection is necessary, but not sufficient.

This is why the majority in the control group didn’t improve in their responses.

Self-reflection needs to be paired from specific inputs by someone who knows how you do, what you do.Focus on the micro to get to the macro.

Most education and training efforts start with the macro by introducing the theories before drilling down to the specifics. Borrowing from uber-learner Josh Waitzkin, it makes more sense to start from the minimal specifics, and then, inductively get to the governing principles.The quality of the feedback will determine the quality of learning.

The type of feedback really matters.

In order to circumvent “performing to the test” and performance anxiety, we made the decision to not provide the scores to participants in the study i.e., how well they performed.

Instead, we focused on providing learning feedback.

This is why, while client’s feedback, session-by-session can be really useful for us to adapt and calibrate to each person, it is not the same as getting individualised feedback from a supervisor/coach who knows where you are at, and where you need to grow.Take another example from our previous Frontiers Friday #202. Peer feedback seems to make things worse.

Can "Deliberate Practice" Make Things Worse? Frontiers Friday #202 ⭕️

There has been a proliferation of deliberate practice studies in the field of psychotherapy. It’s hard to keep up.

Where do you get your learning feedback from?Principles, Not Methods.

> “One has to investigate the principle in one thing or one event exhaustively... Things and the self are governed by the same principle. If you understand one, you understand the other, for truth within and the truth without are identical.”

— Er Cheng yishu, 11th century.

Principles help organise the mind into a hierarchical mental representation of ideas. In some ways, it is like chunking.Once you hit on a first principle, techniques and methods abound.

For more on Principles, see these: For more on the topic of first principles, see this.

Illusion of Understanding.

Last, any time you try to break things down into its component parts, do not be surprised that at first, it seems like you know less than you do. This is called the illusion of explanatory depth (IOED).

This is important to know because, if you are going to attempt to overcome automaticity and your OK plateau, you’d have to face your IOED demons.Thanks for reading.

Once again, here’s the link to the full access of the study.

Notice Board

The DP Cafe has kicked off. We are super-invigorated to meet clinicians from the world over, invested in doing things better.

Welcome to new readers of Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD). Feel free to go through the back catalogue. I’ve done a summary of writing in FPD for the last dacade here. (Six parts).

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, and the latest book The Field Guide to Better Results. Plus, the forthcoming new book, Crossing Between Worlds.

If you are an educator, I highly recommend reading Bob Haskell’s book, Transfer of Learning.