Can "Deliberate Practice" Make Things Worse? Frontiers Friday #202 ⭕️

The short answer is yes, it can. And there are two things to learn from this.

There has been a proliferation of deliberate practice studies in the field of psychotherapy. It’s hard to keep up.

A recent Swedish study caught my attention.

Häkan Lagerberg and colleagues looked at the effects of an eight-week manualised deliberate practice course, aimed at boosting therapists ability at alliance formation in their naturalistic clinical setting.

This pilot study randomised 37 therapists in Sweden comparing a DP group vs. a control group i.e., waitlist. As a primary measure, they used the Session Alliance Inventory (SAI), which is a shortened version of the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI). Therapists saw patients in their naturalistic work setting; the SAI was employed as a pre-post measure of the working alliance.

So what did they do in the two month DP Intervention Group?

In each of the 75 mins weekly online group sessions, a prescribed targeted skill was introduced, followed by 55 mins of role-plays and ended with reflection.

Here’s more about the role-plays:

During the role-plays, the participants were divided into groups of two or three in separate breakout rooms. They took turns playing the roles of client, therapist, and observer. The client role-played the vignettes, and the therapists attempted to give an authentic response in line with the skill criteria being practiced.

Within the peer-group,

the observer and the client gave feedback to the therapist based on the skill criteria and their own observations. After receiving the feedback, the process was repeated, maximising repetition and feedback exposure for the therapist.

Here’s an example of the two of the targeted skills:

Results

Here’s what they found:

Therapists in the DP group experienced a decrease in patient-rated alliance scores, and therapists in the control group showed improvement.

What!?

Let’s pause for a moment, and think this through…

Why is this the case? How could a DP training have a negative impact on client engagement, when the training was aimed at improving engagement?

First, I applaud Lagerberg and team for publishing this study. Too often, negative findings get shelved and we don’t see the light of day of its results. Null or negative findings teach us things we might take for granted, that normally don’t reveal itself in usual circumstances.

Here one of the things this important study reveals:

Peer feedback without a coach to guide is likely to limit, confuse or even impede learning.

Based on the data from this study, it seems like peer inputs messed up their ability to engage normally as they would.

Deliberate Practice Defined

Let’s zoom out for a second and reexamine our proposed working definition of deliberate practice1.

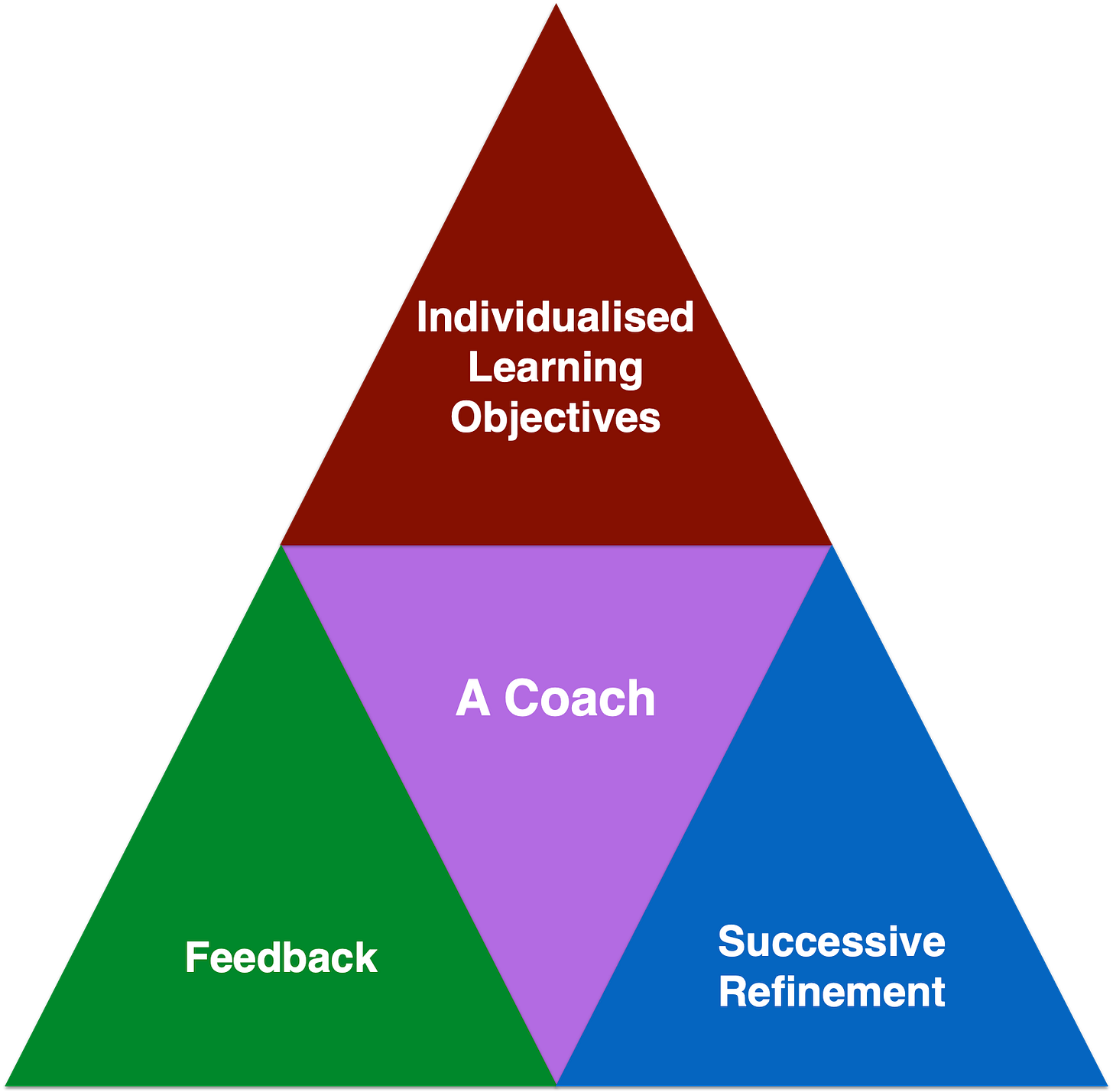

In a nutshell, DP has four critical elements:

Here’s what the late K Anders Ericsson said,

Seen from another angle, any DP efforts must help each learner improve at each of their own zone of proximal development.2 We must help each therapist move from their comfort zone and into their learning zone, while being mindful of not tipping them into their panic zone.

For more about deliberate practice, see related posts:

Okay. Now that we have these concepts loaded into our minds, let me zoom in and focus on two issues at hand:

Types of Feedback

Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Learning

1. Types of Feedback

In our Difficult Conversations in Therapy (DCT) Project (more on this in the near future), we employed the four pillars of DP, aimed at helping therapist dealing with challenging scenarios that typically occur in clinical practice. We learned the following:

The quality of the feedback determines the quality of learning.

Not all feedback is created equal.

Plus, I make a distinction between performing feedback and learning feedback3:

Performing feedback is evaluative, i.e., how well you did. Learning feedback, on the other hand, is descriptive and specific, delivered in manageable chunks in order to assist the practitioner to reach just beyond their current ability, i.e., learning zone.

We can infer that likely, the feedback delivered by peers in Lagerberg et al.’s (2024) study didn’t exactly help in their learning process. (It would be interesting if there were self-reports from therapists during the process. In our DCT project, self-ratings from therapists in the feedback group experienced more difficulties and an even a perceived decrease in performance, compared to the control group—even though they were improving in their abilities!)

Feedback from Supervisors

But even if feedback is not delivered by people in the same boat as you (i.e., your peers), an “expert” or your clinical supervisor, needs to deliver specific feedback that helps you at your growth edge. And in order to do so, they have to know your work. Said in another way, your supervisor has to build upon your existing ability, instead of superimposing what you “should” be learning.

This is hard. Because it means that your clinical supervisor has to know how you do what you do in the therapy room, develop an individualised learning direction to take, and help you take successive steps towards this learning goal.

Case in point: Notice how much evaluative feedback we tend to give and receive (e.g., that’s good. Keep it up. Good on ya!”

What does a good coach do instead?

In a study examining what the legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden does in his teaching practices, the researchers said,

We conclude that exquisite and diligent planning lay behind the heavy information load, economy of talk, and practice organisation.4

How exactly does this look like on the ground?

Wooden spent so little time dispensing praises or reproofs, and the majority of the training with his players giving specific instructions, what to do and how to do.

This is relevant to the topic of feedback. We can only provide this level of nuanced feedback if we can assess where someone is at, and where they need to grow.

2. Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Learning

This is where a debate might be lurking.

In Lagerberg et al.’s study, a list of set skills are pre-defined. This is similar to most existing pedagogical approaches to traditional teaching. You provide a list of common-core objectives and you strive for the learners to meet the mark.

This top-down approach resembles more like what Ericsson might call Purposeful Practice.

There is a place for purposeful practice. But I’m not sure if this should be conflated with deliberate practice, which is much more individualised, and learning objectives are determined based on the learner’s baseline ability, i.e., bottom-up approach to learning.

In a sense, purposeful practice is like building LEGO with fixed instructions and specific design to build. Deliberate Practice, on the other hand, is like the original LEGO—it’s up to you on what you choose to build. The former is much easier, but the latter is ultimately more fulfilling.

Get back from LEGO into psychotherapy, I see it this way: purposeful practice aims for competency, whereas deliberate practice aims for excellence.

Rod Goodyear, Bruce Wampold and colleagues argued that the most meaningful definition of expertise should not be based on expertise in therapist performance, but it must be anchored in improvement in performance in client outcomes.5 In the learning sciences, this is often called “transfer of learning.”

Conclusion

As the field conducts more empirical studies into DP and its effects on performance in psychotherapy, I hope that we use the four pillars of DP as a working definition that can be built upon (and tear down) when needed.

History does not have to repeat itself.

Notice Board

Big thanks to good people of the Association of Counselling Psychologists (ACP) for having me at their conference last week.

I talked about "Seven Ways Deliberate Practice Can Go Wrong.” I am hoping to have post the recording into our podcast in a couple of weeks time. Stay tuned.

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, and the latest book The Field Guide to Better Results.

Miller, S. D., Chow, D., Wampold, B. E., Hubble, M. A., Del Re, A. C., Maeschalck, C., & Bargmann, S. (2018). To be or not to be (an expert)? Revisiting the role of deliberate practice in improving performance. High Ability Studies, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2018.1519410

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Chow, D. (2017). The practice and the practical: Pushing your clinical performance to the next level. In D. S. Prescott, C. L. Maeschalck, & S. D. Miller (Eds.), Feedback-informed treatment in clinical practice: Reaching for excellence(pp. 323–355). American Psychological Association.

Ronald Gallimore, & Roland Tharp. (2004). What a coach can teach a teacher, 1975-2004: Reflections and reanalysis of John Wooden’s teaching practices. The Sport Psychologist, 18(2), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.18.2.119

Rodney K. Goodyear, Bruce E. Wampold, Terence J. G. Tracey, & James W. Lichtenberg. (2017). Psychotherapy Expertise Should Mean Superior Outcomes and Demonstrable Improvement Over Time. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(1), 54–65. https://doi.org/doi:10.1177/0011000016652691

I like this part Daryl about coach John Wooden: "Wooden spent so little time dispensing praises or reproofs, and the majority of the training with his players giving specific instructions, what to do and how to do.

This is relevant to the topic of feedback (to psychotherapists). We can only provide this level of nuanced feedback if we can assess where someone is at, and where they need to grow."

We can't assess where a therapist is at unless they're routinely monitoring their outcomes in every session with every client. Next they share their data with their coach; who creates individualised learning objectives for them; gives specific, actionable feedback on its implementation; and successively refines their learning objectives.