How You Can Overcome Automaticity: The Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice (Part II) Frontiers Friday #185 ⭕️

The backstory of the TDPA, the pitfalls, and how you can overcome the OK Plateau.

Note:

If you have missed last week’s missive, feel free to go to FF184 to download your free copy of the Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice (TDPA) worksheet, plus the googlesheet version, which helps you track your progress and guide your focus over time.

I hope to give you a bit of a backstory, the specific struggles we faced in the development of the TDPA, and the stuff you can do to help yourself. I also hope it’s not too much of an indulgence to go back in time to share with you some of my ups and downs with the development and the use of the TDPA as a practitioner. Perhaps it might help you as you embark on your endeavour.

But first…

Guidance On Using the TDPA

Before we get into the backstory, to help you dive straight in, we have made one of our videos from the Deliberate Practice Web-Based Workshop freely available to you. It goes into more details on how to use the TDPA.

I hope you find this useful.

Genesis of the Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice (TDPA)

The Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice Activities (TDPA) worksheet was conceived for a self-serving purpose.

During the period of 2010-2014, after studying the field of expertise and expert performance in all sorts of domains for some time, I was totally overwhelmed. By then, I have been in the field for about a decade, and I was still thinking, There is just so many aspects I need to be working on!

Do I go deeper into emotion-focused therapy? What about learning more from a psychodynamic perspective… Oh, and would learning more about attachment-based work help? What about coherence therapy? Wait, everyone else is talking about trauma-focused and compassion therapy…And am I really screwing myself over for not going further with the so called “gold-standard” of CBT?

RELATED ARTICLES AND VIDEO:

Depths of Excellence and Ethics. Frontiers Friday #150 ⭕️

People don't care how much you know until they know how much you care. ~ Coach John Wooden, from You Haven’t Taught Until They Have Learned, p.9 I’ve been chiseling at this for far too long. Since late January 2021, I’ve been trying to figure out a way to articulate what I’m about to describe in today’s post.

A Step Forward… Into Overwhelm.

But from everything I was learning so far, those questions I was asking myself were not good questions to begin with. Taking all into account, the existing evidence would suggest that I was barking up the wrong tree.

I have a tendency to obsess with the HOW before I address the What.

What in the world should I be working on?!

Moreover, unlike other fields like chess, sports, and classical music that I was learning about deliberate practice, psychotherapy was somewhat different. The environment was not so “kind” (i.e., the feedback loop for the target of learning and the impact of performance are clear). Psychotherapy seemed to fall in a less kind environment, or what Robin Hogarth would call, Wicked Environment (i.e., the rules of the context are often unclear, and the feedback loop for the target of learning and the impact on the performances are delayed, inaccurate, or both. Other examples of wicked environments: poker, soccer, medicine, life).

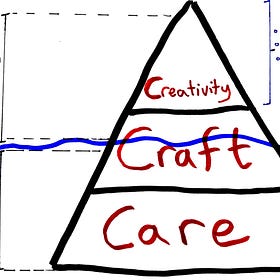

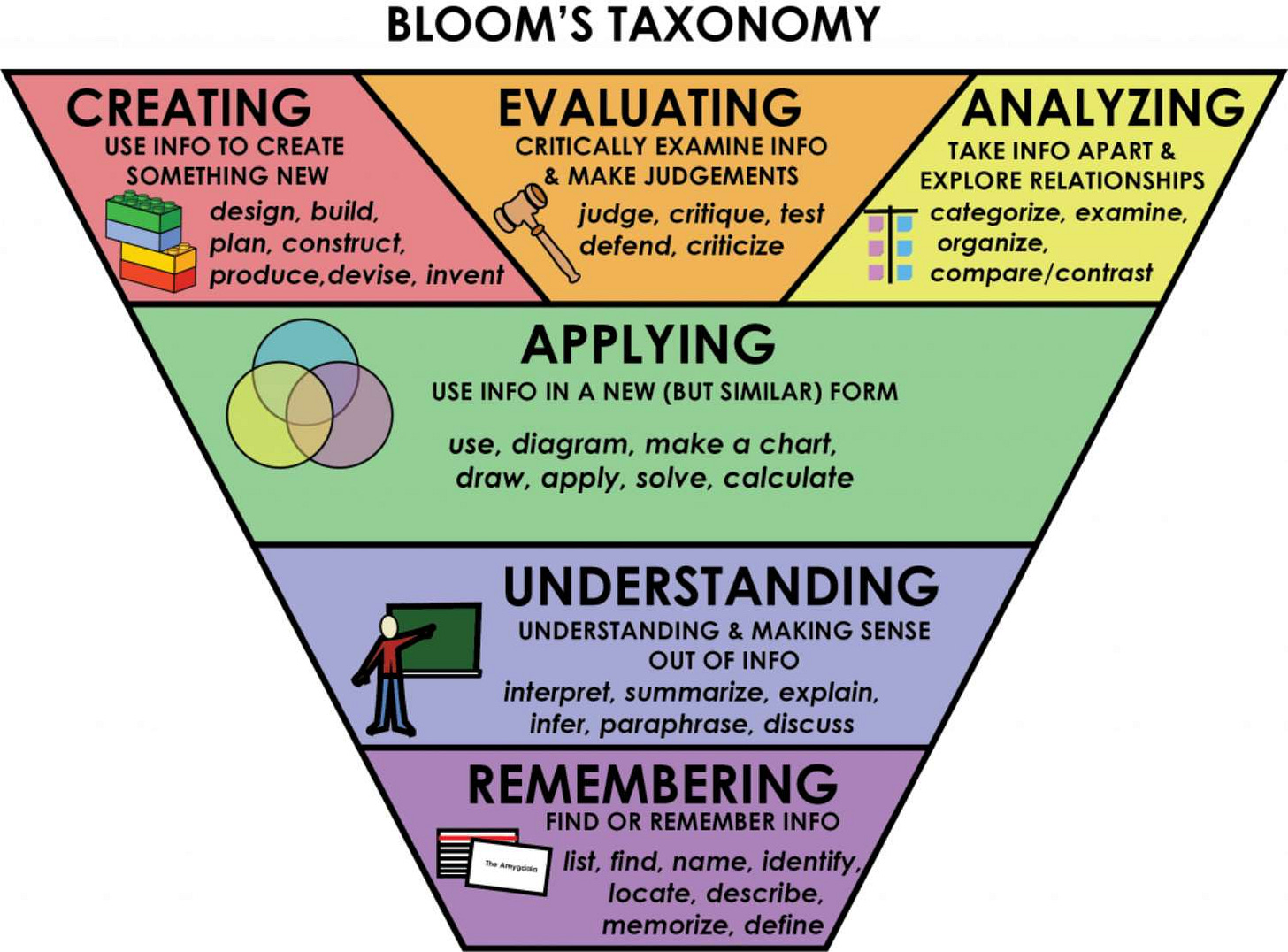

Then I got inspired by something I stumbled across in the learning literature. It was Benjamin Bloom’s Taxonomy, a framework through which teachers use to guide their students through the cognitive learning process.

So I thought, Easy, I should do something like this for the therapy and simply break it down into parts, so that I can work on it.

I didn’t expect that I would become somewhat snowed under with how to even begin doing this.

One dimension I took was to break the therapy hour down into chunks.

Beginnings:

How do you begin a first session? How do you begin a subsequent session? How do you induct someone into therapy?

Middles:

How do you deepen the process?

How do you tap and utilise client factors, their resources, their Why’s?

Endings

How do you close a session?

How do you create an impactful closing?

How do you gather feedback to feed-forward into future sessions?

This to me, was a good start. But something was missing. This felt flat, lifeless, and two-dimensional. I soon realised I need to add the other "hidden” dimension in the therapy process. The stuff that is “felt, not seen” within the hour of deep conversation, e.g., attunement, emotional vibrancy, dealing with minor and major mis-alignments, the mobilisation of the will of the client, the use of the self, etc.

I listed all these down.

I didn’t expect that it would cast even more doubt about my ability as a therapist.

I later learned that this was actually to be expected. I chanced upon a study by Rozenbilt and Keil (2002) called, The Misunderstood Limits of Folk Science: An Illusion of Explanatory Depth.

To get a sense of what the Illusion of Explanatory Depth or IOED is about, here is a thought experiment:

How well do you know how a toilet flush works? Rate that from a 0 to 10. Now, take a piece of paper and explain it through step-by-step, how does a toilet flush work. Again, rate this from a 0 to 10.

How well do you know how a bicycle works? Rate that from a 0 to 10. Now, take a piece of paper and explain it through step-by-step, how does a bicycle work. Again, rate this from a 0 to 10.

Chances are, your rating is likely to dip.

This, is the IOED.

Who Not How

I didn’t know how to proceed further. I had fell into IOED. It felt like a pointless hole to fall into. Who would even give a damn about this?

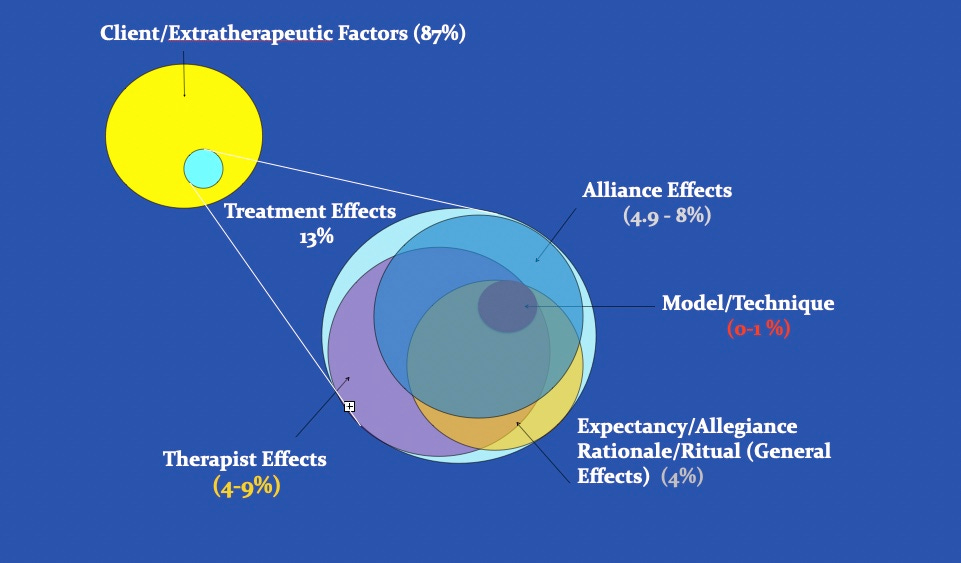

This was when Scott Miller offered me some perspective hit the nail in the head. In one of our late nights (his early mornings) Skype calls, he said, “I think we can map this across the therapeutic factors.”

This was what Scott meant when he said ‘therapeutic factors’:

FOR MORE ABOUT THERAPEUTIC FACTORS:

We began to collaborate and flesh out a better version of this, crossed-map to what others like Bruce Wampold have found through the past few decades of psychotherapy research.

If Scott wasn’t in the picture, I doubt the TDPA would have seen the light of day. It would probably be just a little document/spreadsheet existing in my PC.

This taught me something: Everyone needs a WHO.

Scott was the WHO before we could take it further to where it is today (at version 6).

Chase Two Rabbits, and You’d Catch None.

We got underway to develop and refine the TDPA worksheet.

Frankly, Scott had more faith of its utility than I did. I thought to myself, he must be seeing something that I don’t.

The next road-bump was somewhat embarrassing. On 10th of November, 2015, I had examined my outcomes, revisited my caseload, and completed my own TDPA. Then I narrowed down to 3 THINGS to keep focused on and improve:

Elicit nuanced feedback

Conveying explicit care

Suggestion for homework/tasks between sessions

Looking back at my baseline performance, I was pretty happy about this plan.

Three weeks later, I had completely forgotten about what those 3 THINGS were. Ugh.

Meanwhile, Scott and I were running our annual Deliberate Practice intensive workshops in Chicago. We learned others had similar experiences of losing track of the focus, or feeling overwhelmed. While working on three things seemed manageable, in reality, it was still too many, when you consider the multi-faceted lives many of us have.

On 25th of January, 2016, I conceded and noted to myself,

“Very hard to focus even on just three things! Need to narrow it down to just one.”

This was a small but significant insight. I have to focus on ONE thing, not two, and certainly not three.

I recalled the saying, Chase two rabbits and you catch none.

It is humbling to be struck by the law of diminishing returns, which is probably as real as the law of gravity. The law of diminishing returns is that the more goals you have, the less you are able to achieve it.

My One Thing Over Time

Over time, as I meandered through and continued my clinical practice and sought guidance from supervisors and books, here wad the ONE thing I was focusing on at different stages:

12th of Apr’16: Tap and utilise client resources to heighten engagement.

7th of Aug’16: Re-contact supervisor as I was losing track of where I was going.

27th of Feb’17: Re-devote to once a week reviewing specific parts of therapy recordings, plus get supervisor to watch.

27th of Sept’17: Consolidate what I’ve learned so far. I also began to incorporate the idea of “Anti-Goals” at this stage, i.e., What not to focus on. This is to curb any short-term overly-caffeinated optimism I might have to work on more.1

22nd of May’18: To be less formal; more personable. (Looking back, this was a significant thing for me, as I found myself somewhat unwittingly becoming cold and clinical in-sessions).

24th of July’18: Balance between being strategic/coachy and emotive.

24th of Oct’18: Same thing. Balance between being strategic/coachy and emotive.

26th of Feb”19: Mobilise the will of the client before going further. (Otherwise, I become the one doing all the heavy-lifting in sessions and still not making progress)… (Flash forward)

Current: To allow myself to be more expressive and less inhibitive in-session.

What is the Big Deal Anyway?

The TDPA is not going to bring world peace.

Neither will it answer all of your professional development woes. In fact, as you can tell by now, the TDPA might first inundate you, cast shadows of doubt upon you, and if you see it through, it will provide a light forward, for the rest of your professional career.

The TDPA serves as somewhat of an antidote the problem in our field. I have previously addressed some of the pressing issues at hand in our field that has relevance to the existence of the TDPA. In gist, there are inherent problems in the way we train, supervise, and perceive about the influence of clinical experience.

Read this:

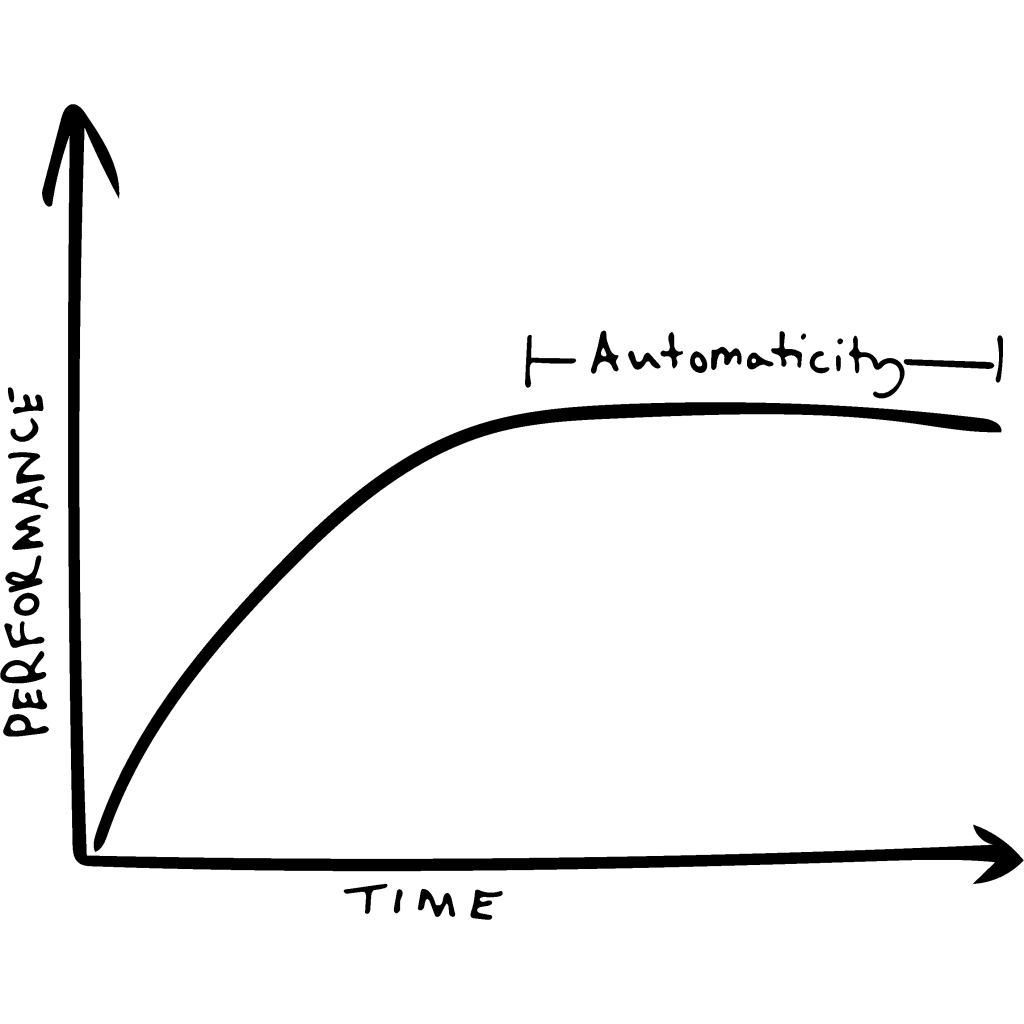

As we cumulate clinical experience, one of the challenges we face is to overcome automaticity, or sometimes referred to as The “OK” plateau.

Our hope is that the TDPA helps you counteract the “OK” Plateau. You will likely become conscious about what you are doing. But the aim is not to stay conscious about it, it is part of the cycle to then move what you’ve acquired into the unconscious.

The Work Before the Work

The night before I visited my dentist, I flossed my teeth, twice.

What we do before the work, "the work before the work" matters a great deal.

It has once been attributed to Lincoln who said,

If I had eight hours to chop down a tree, I'll spend six hours sharpening the saw.

Take the time to figure out WHAT to work on before obsessing about the HOW.

If you are interested to be on the waitlist for the next Deliberate-Practice Web-Based Workshop, please email me at admin@darylchow.com with the title: “Waitlist for DPW.”

P/S: You might be interested in the latest post on my other Substack, Full Circles: Reflections on the Inner and Outer Life, on “Don’t Lose Your Humour.”

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, and the latest book The Field Guide to Better Results.

The anti-goal idea turned out to be a critical feature. Makes any effort in improvement more sustainable in the long-run.