Frontiers Friday #133. Common Therapeutic Factors (Part I) ⭕️

From music to psychotherapy. Ode to one of the leading lights in our the field of psychotherapy.

By temperament, I’m not exactly a conscientious person nor academically inclined. Compared to my two sisters, I was probably the one who struggled the most in school, quick to quit on tasks, and the one who contributed to the greatest amount of mess in the household.

But when I was about 14, the day that Diony brought his flying-V guitar to school, plugged into a mini-Marshall amplifier through his metal zone boss pedal, and flawlessly riffed Metallica’s Master of Puppets, I was forever changed.

“How is it possible that sound was coming out through that thing?”

I became obsessed. Diony was way too cool to be my friend. We were teenagers. So I approached Winston instead. Both of them were a few years older than me. But Winston was eager to show off his chops. So I hounded him, everyday, after school.

Winston taught me the magic bar chords to Guns N’ Roses One in a Million.

For the first time in my life, I became obsessed. I now cared about something. I wanted to make those sounds that Dionne and Winston were able to conjure up from the gods.

And before I could play more than 4 chords, 4 seniors in the school and I formed a band and knuckled down an original tune—with 4 chords. We unabashingly called ourselves The Hindenburg (named after Led Zeppelin). We soon realise how unoriginal we were, and made a couple of band-name changes. We continued to play together for more than 15 years.

Go to the Source

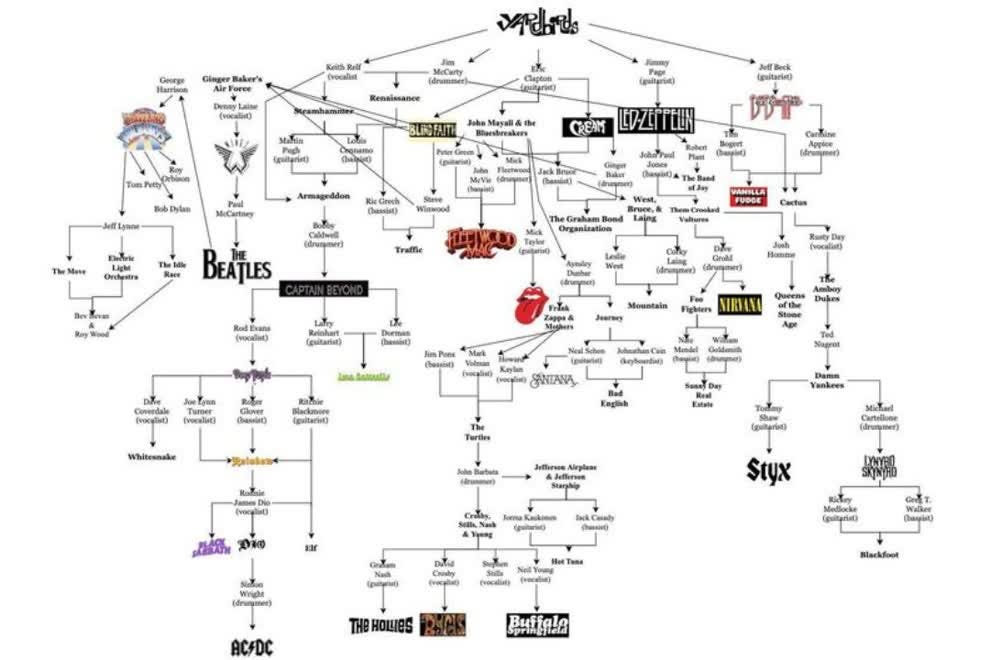

I didn’t realise it then, but it only dawned upon me a few years ago, that one of the key principles I picked up from my love of music was to “go to the source.”

Who influenced Pearl Jam? Go to The Who and Neil Young.

Who influenced The Verve? Go to the roots of shoegazing with the likes of Cocteau Twins.

Who influenced Wilco? Go to Americana and the Beatles (all road leads to the Beatles… so who influenced the Beatles…).

…And so it goes.

Going to the source was not so straightforward in the 90’s. We didn't have Spotify or music streaming services. We had cassettes.1 Paradoxically, this scarcity of not enough lunch money saved to buy that Led Zeppelin III album made me and my friends savor things more. We heard side A and side B, on repeat. We traded tapes. We made mix-tapes. And then we listen--again. You start to hear things you didn’t previously hear.

Transfer of Obsession

My obsession in music spilled into other aspects of my life. I didn’t intend it to be, but it bled into the way I learned things.

School told us what to learn, but in life, you have to figure out what to learn.

After I came out of the Army, which is a mandatory conscription for males for 2.5 years in Singapore, I worked as a youth worker, and I was lucky that I had mentors who encouraged my thirst to dig deeper into things.

But I was troubled in the process of my post-graduate program in psychology. All these textbooks and research articles we were told to read, felt incomplete. It was CBT this, and CBT that. Then this “third wave” movement came, and then it was “mindfulness” this and “mindfulness” that, and “ACT” this or “ACT” that.

Even as innocuous as this was, one time in a group psychotherapy class, I had learned from somewhere that a book by Irvin Yalom on group psychotherapy dynamics offered a different perspective from the textbook that we were reading. I asked the lecturer what she thought about it. She said to me, since the group work and the assignments weren’t be based on Yalom’s views, I should focus on the prescribed textbook instead.

I was slow to realise this, but it became clearer to me that education was a game. And grades are points to that finite game. I had to make the choice if I wanted to play it. Because this game has a trifecta of requirements, namely intelligence, conscientiousness, and conformity2

I wasn’t so smart as my sisters. But I could feel my so-called conscientiousness to “get my shit together” bubbling in me—but for the life of me, I’m not one who is compelled to conform. I couldn’t force myself to do what I was told, or learn what I had to learn, so as to make the grade.

Enter Bruce Wampold.

From Music to Psychotherapy

I first read The Heroic Client around 2004-5. This book written by Barry Duncan and two of my co-authors, Mark Hubble and Scott Miller, had a huge influence on me.

Taking the principle of “Go to the source,” Heroic Client led me to the work of prolific researcher from University of Wisconsin, Bruce Wampold.

His book, The Great Psychotherapy Debate, edition no. 1, single-handedly unblinded my eyes. He opened an entire world within a world.

It was like reading a mystery novel. I went through the book repeatedly. To the displeasure of my wife, I brought that book along to our honeymoon in New Zealand. “Honey, I’m sure the landscape and mountains are much more enchanting that what Prof. Wampold has to say.”

Wampold unraveled a truth that can only be seen if you zoomed out just enough to get a sense of the landscape. He peeled behind the medical model of how most of us are trained to think, which tends to focus on identifying Treatment X for Disorder Y through using Specific Model Z.

Wampold provided a compelling alternative of which he called the Contextual model, which considers the broader influence of what impacts therapeutic change.

Some Explanations:

To make sure we are all on the same page, let me briefly explain what common factors and the Dodo bird conjecture means.

1. What are the Common Factors in Psychotherapy?

Common factors refer to the shared elements that are present across different types of psychotherapeutic approaches and contribute to therapeutic effectiveness. This include things like the therapeutic alliance (the relationship between the therapist and client), the client's expectations for treatment, the client's level of involvement in the therapeutic process, and the therapist's empathy and warmth. These factors have been found to be consistently associated with positive therapeutic outcomes across different types of therapy.

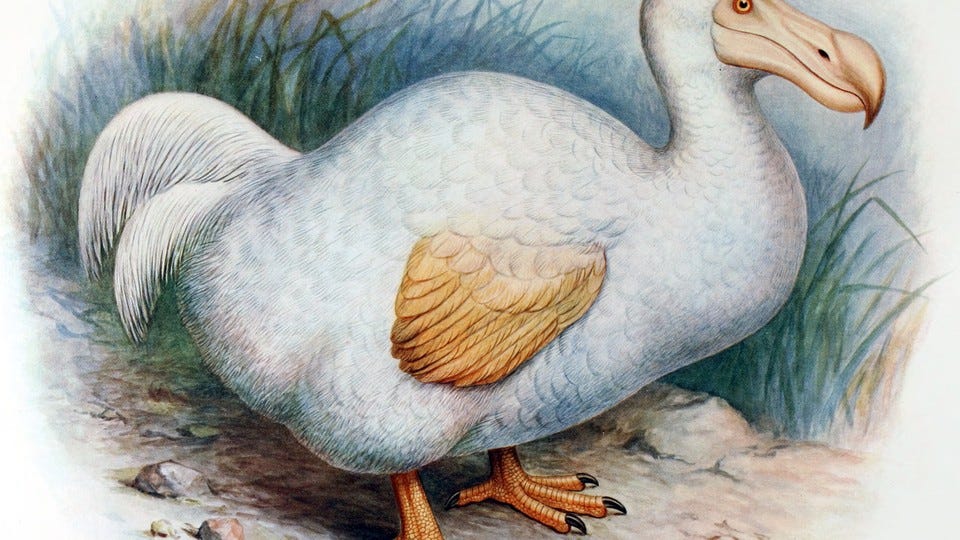

2. What is the Dodo Bird Conjecture?

The Dodo bird conjecture is the idea that all psychotherapeutic approaches are equally effective, meaning that different forms of therapy are essentially equivalent in terms of producing positive therapeutic outcomes. Reflected by Saul Rosenweig in 1936 as he borrowed from Alice in Wonderland, “At last the Dodo said, ‘Everyone has won and all much have prizes.’”

Key Discoveries

To get a sense of the composite findings that Wampold and colleagues had gleaned from the body of literature in psychotherapy, here’s an overview taken from The Great Psychotherapy Debate:

It seems that after all the hundreds of studies, and millions of dollars spent in examining differences in different approaches in various countries, treatment differences accounts for something like less than 1% of the outcome!?

If this is the reality, what on earth are we doing in psychotherapy training? How are we investing appropriately in research? What and how should we be teaching in our higher education?3

I have to admit, I didn’t intend to write about common factors and the Dodo bird today. There’s a full “playlist” of topics I wish to cover, plus contributions from other practitioners I wish to feature. But I just received in my inbox from one of my favourite peer-reviewed journals, Psychotherapy Research. They recently released a series of commentaries on the Dodo Bird conjecture in Vol. 33, Issue 4 (2023), based from a seminal article published by Wampold and colleagues 25 years ago.

Let’s dive in to this week’s Big Five for our Frontiers Fridays, No. 133.

😱 Research: A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: Empirically, "all must have prizes"

This is a seminal meta-analysis. This high-impact study had twice that of the next highest-cited relevant article in the Web of Science (WoS) citations.

Before this 1997 article, previous studies had not conducted true comparisons. Take, for instance, 8 out of 13 so-called “dynamic-humanistic” studies used for treatment comparisons did not actually contained therapeutic elements and “could be viewed as a straw man” (Shapiro & Shapiro, 1982, p. 591).

Also, comparing with a wait-list or no-treatment, isn’t exactly good enough. Something is often better than nothing.

Wampold et al. define what a “bona fide” psychotherapy comparison:

“…those that were delivered by trained therapists and were based on psychological principles, were offered to the psychotherapy community as viable treatments (e.g., through professional books or manuals), or contained specified components.”

Key Graf:

- “The results of our analysis demonstrated that the distribution of effect sizes produced by comparing two bona fide psychotherapeutic treatments was consistent with the hypothesis that the true difference is zero.”💬 Commentary: Brave new world: Mental health services 25 years since Dodo and 25 years in the future

Here’s Wampold commenting on their article in 1997.

Key Graf:

- “I am skeptical of improving services by implementing purportedly superior treatments in a system of care, based on a randomized clinical trial, because

(a) the results often defy reasonable explanations,

(b) implementing results from clinical trials in other contexts is fraught with difficulty,

(c) psychotherapy trials rarely if ever are replicated,

(d) differences among therapists, due to their clinical skills, are more important than differences among treatments, even if a treatment is demonstrably (but marginally) better, and

(e) such implementation reduces therapist and patient preferences and leads to therapist discouragement.

- The designation of the RCT as the gold standard of psychotherapy research has set us back decades—to wit, identify one clinically actionable conclusion from RCTs, which by the way have cost hundreds of million of dollars.”💬 Commentary: Smaller effects matter in the psychological therapies: 25 years on from Wampold et al. (1997)

Michael Barkham highlighted an interesting point about the value of systematically monitoring outcomes:

- “Consider a recent large meta-analysis reporting an overall ES d of 0.15 for routine outcome monitoring, increasing marginally to 0.17 for patients not-on-track (de Jong et al., 2021).

- While classed as a small effect, it is additive to the existing overall effect of psychotherapy (i.e., it is an effect over and above the general effect of psychological therapies).”💬 Commentary: The implications of the Dodo bird verdict for training in psychotherapy

Given my struggles in the formal education process, training and learning is one area I deeply care about.

Henny Westra raises some unsettling findings about the current state of training in the field of psychotherapy:

- “there is no evidence that continuing education workshops… produce sustained skill development—quite the opposite.

- Large effects on self-report are found but any modest improvement in performance erodes over time without further coaching.”⏸ Words Worth Contemplating:

“It’s not enough to rage against the lie. You’ve got to replace it with the truth.”

~ Bono, U2.

Reflection

Take another look at the Table above taken from The Great Psychotherapy Debate. What strikes you?

Where have you been investing your time, money and effort in your professional development?

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, and The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, and the forthcoming book The Field Guide to Better Results .

The Field Guide to Better Results is coming out soon on 23rd of May’23!

When CDs came into the market, it was both a blessing and a curse. The sound quality was so much better, but it costs more than double that of cassette tapes.

From A Case Against Education by Bryan Caplan.

We have just done a study examining the dissonance between what students are taught in their program and what the evidence actually is. We hope to get that story out soon. In gist, some students are pissed.