Helping Someone in the Face of Suicidal Risk #216 ⭕️

The stuff that keeps us awake at night.

I’ve been meaning to return to addressing the outline laid out in Maps of Knowledge.

For me, suicidality sits moderately high in terms of content knowledge (i.e., Knowing what to do) and challenging in terms of process knowledge (i.e., how to engage with someone in a meaningful way).

How do you work with a suicidal client?

“Are you thinking of hurting yourself?”

Early in my career, when assessing for suicidal risk behaviours, I found myself saying, “Are you thinking of hurting yourself?”

When I listen to other therapists’ session recordings, this is a very common way we seem to get to get around entering into the topic of suicidality.

But this question can be problematic.

In her book, Helping the Suicidal Person, Stacey Freedenthal shared a vignette:

Siobhan, a counseling intern, was so afraid of talking about suicide that she dared not speak the word. It was almost a superstition: “If I say the word, it makes it more likely to happen,” she said. So she was ill-equipped to respond well when Jamar, a 14-year-old teenager, told her, “Sometimes I just don’t care about anything. Nothing seems to matter anymore.”

“That sounds so difficult,” she said. She wondered if he wanted to kill himself, but her anxiety intruded. So she used a euphemism favored by many people: “Are you thinking of hurting yourself?”

“No way!” he said emphatically. “I’m already hurting enough.”

Soon after the session, Jamar wrote a suicide note to his parents and took a bottle of ibuprofen. His younger sister found him unconscious in his bed, and he was taken by ambulance to the hospital.

At his next session, Siobhan said to Jamar, “I’m confused. Please help me to understand so I can do better. I asked you if you wanted to hurt yourself, and you said no.”

“I didn’t want to hurt myself,” he said. “That’s why I took pain pills, so that I wouldn’t feel any pain.” Siobhan had learned an important, almost fatal, lesson about the need to speak frankly about suicide.

So how do you go about assessing not just the suicidal risks, but also understanding how the person got to this point in their lives, and what we can do to help them?

In Part I of this series, I’m going to share five tips (and a bonus) offered by Stacey Freedenthal’s immensely helpful book.

Embrace a Narrative Approach: “Suicidal Storytelling"1

Most professionals ask about risk, and not about the background that led to where they are now.

Freedenthal shares a client’s perspective on this,

“They often have asked if I was suicidal. Some even asked why. But not in the way you did. Instead, they wanted to know all about my suicidal thoughts, but not really about me. And when I’d say no, do not worry yourself, I’m notgoing to do anything, they basically changed the topic. Almost as if they

were covering themselves, do you know what I mean?”

Questions you can ask:

- “Could you tell me how you got to the point that you wanted to put an end to your life?”- “I would like you to tell me the story of what led to the suicidal crisis. Just let me listen to you.”

- I would like to understand more about your background and what got you to here…

Ask About Suicidal Imagery, Too.2

Some clients might report no suicidal thoughts but on further exploration, it may turn out that they picture themselves in the act of suicide or it’s aftermaths, or what is called “flash-forwards.”

Imagery of suicidal acts reveals how intensely the person considers suicide,

but it is important to assess imagery for another reason, too. Mentally rehearsing killing oneself can make the image—and the act of suicide—less distressing over time. The person gets used to the idea, maybe even more drawn to it.

Do Not Use a No-Suicide Contract3

Some of you know this already, but admittedly, when I started off my career in psychiatrist hospitals, this was still taught and used.

No-Suicide contracts feel more like managing our own anxieties—and ass covering—rather than helping the person at risk.

Jerome Kroll said, “Attempts to pressure a suicidal patient whom one barely knows into making a no-suicide contract could be interpreted by the patient as a clinical retreat into legalisms rather than an expression of genuine concern.”

Freedenthal states, “There is little evidence that no- suicide contracts work. Instead, there is evidence that they do not work.”

She goes on to cite studies showing that 65% of psychiatric inpatients who attempted suicided whilst in the hospital had agreed to a no-suicide contract.

“The inpatients who “contracted for safety” were 5–7 times more likely to attempt suicide than those who did not.”

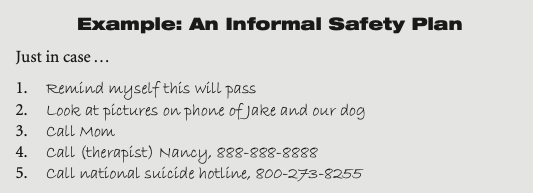

Collaboratively Develop a Safety Plan4

What is the alternative to contract? A Safety Plan.

“The development of the safety plan is perhaps the single most important activity that occurs in the early sessions of treatment.” —Amy Wenzel and Shari Jager-Hyman (2012, p. 124)

Take care to assess motivation to follow the plan:

- “On a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being not at all and 10 being completely,how likely is it that you will do this step the next time you have thoughts

of suicide?”

- “What would make it hard to do this step of your safety plan?”

Encourage Delay

This is by far, one of the most important piece of advice.

Here’s a related piece from Full Circle’s archive: Do not make a permanent solution in a temporary storm.

Cited in the book, Donald Michenbaum offers a way to address this (i.e., process knowledge):

While suicide is an available option and given your view of your situation that is understandable, it is critical that you allow us some time to work on reducing your emotional pain…. Would you be willing to partner with me and hold off on the suicide option in order to allow yourself the time that is needed to address these issues?

Bonus Tip: Treat Chronic Suicidality Differently

I usually keep to five recommendations for Frontiers Friday, but this one is too important to leave out.

Joel Paris said, “Methods generally recommended for the management of suicidality are ineffective and counterproductive in chronically suicidal patients.”

This is because there is a difference between acute suicidality and chronic suicidality.

The difference in emphasis is one "staying alive’” vs. “having a life.”

Freedenthal says,

Acute suicidality is a time- limited crisis, like pneumonia. Chronic suicidality endures, like diabetes. As a result, chronically suicidal individuals need to take responsibility for managing their challenges.

I highly recommend getting Freedenthal’s book. I’ve only scratched the surface here. Her book has 89 tips!

If you plan to have a career in the helping profession, you are going to one to have this book with you as a companion.

More to come in the coming weeks on supporting others at risk of suicide.

P/S: If this was hard to read, even if you are a helping professional, do reach out for support in your local area. Suffering is wasted when we suffer alone.

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, and the latest book The Field Guide to Better Results. Plus, the new book, Crossing Between Worlds.

You might be interested in my other Substack, Full Circles: Meditations on the Inner and Outer Life.

Tip #10 of the book Helping the Suicidal Person, by Stacey Freedenthal.

Tip #11, Ibid.

Tip #37, Ibid.

Tip ##38, Ibid.