Fixing Holes. #226 ⭕️

Seeing what's not there.

Imagine it’s World War II and you are tasked with repairing military equipment. On this occasion, you are assigned to find the areas on your planes that were most often hit by enemy’s fire so that you can cover them with more armour.

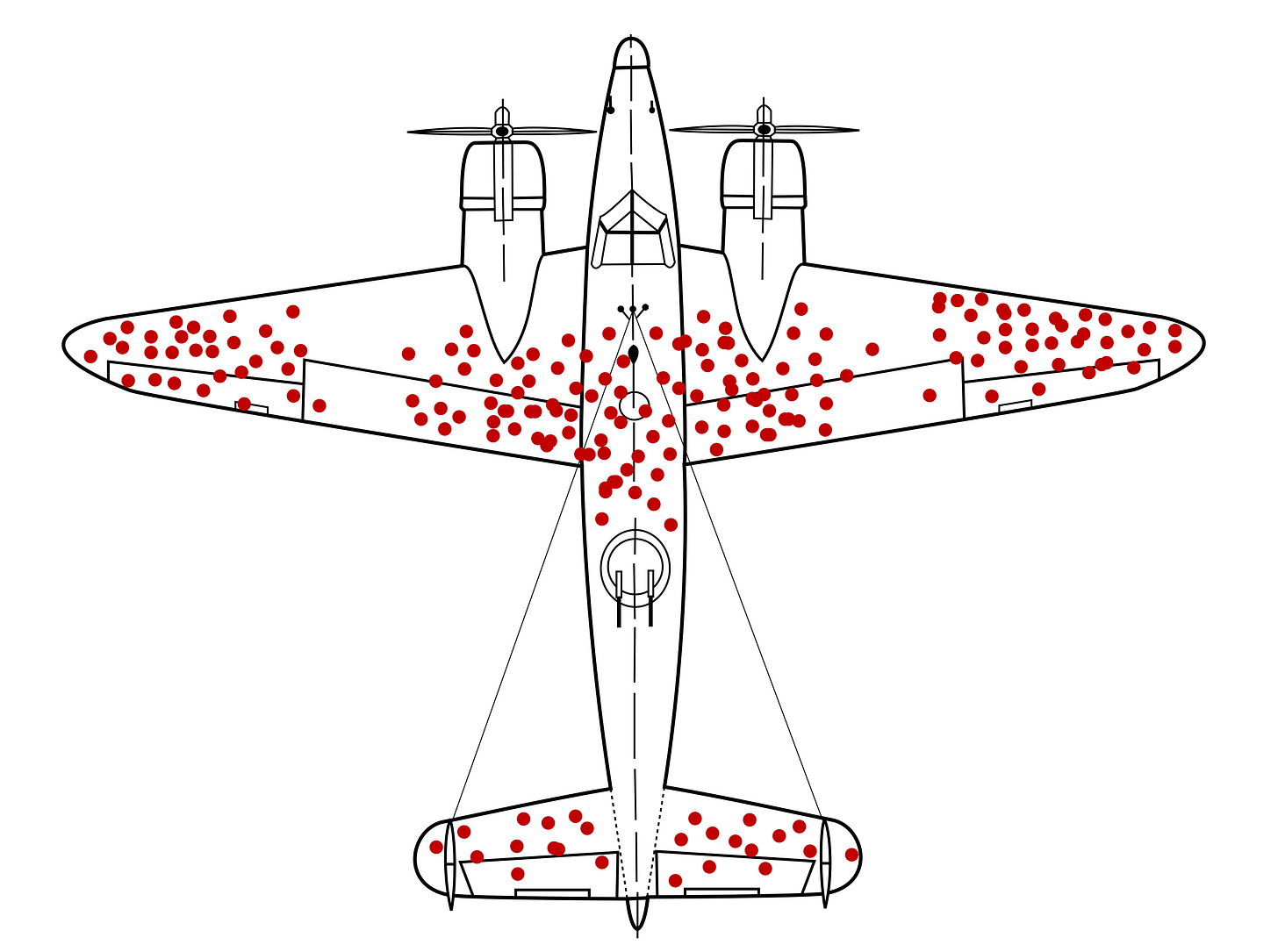

The planes look something like this:

So, like any good military personnel you go ahead and count the bullet-holes.

Which areas would you make the reinforcement?

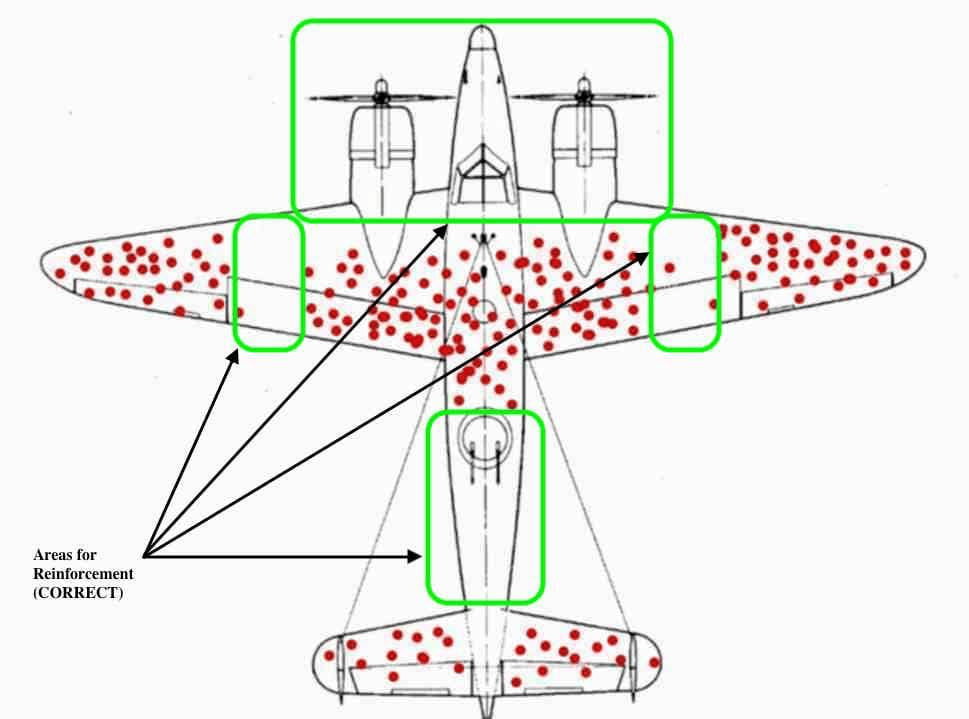

Now, a mathematician comes down from his ivory tower, squeezes past the hierarchy of officers and comes to you and says, “Stop. Stop. Stop. What you are doing isn’t helping. I know what you need to do.”

You scoff at first, but you brace yourself and hear him out. He continues,

“Instead of counting the bullet holes on the returned planes, I recommend that you armour the spots where none of the planes had taken any hits.”

You know he’s right.

Mathematician Abraham Wald’s insight points at a cognitive bias we are prone to: survivorship bias.

Survivorship bias is the logical error we make when we only account for variables that are present, while overlooking those that did not. This mental shortcut can cause us to make wrong conclusions.

We focus on the planes that made it back. We fail to account for the planes that didn’t.

The other planes didn’t make it back because they were hit where they should have had extra protection, like the fuel tank. The returning planes could only show what was less relevant.

RELATED:

Negative Painting

I am no mathematician.

In fact, I failed Math and Chinese in secondary school (which Chinese fails maths and Chinese!?).

I was surprised the first time I heard this airplane example in Ahren Sönke’s book, How to Take Smart Notes, citing Nassim Taleb. Thinking in terms of “what’s not there” is not intuitive—at least to me.

I am no painter either.

But I’m learning to paint. But for the life of me, when brush means paper, even though I intellectually compute the idea, I just couldn’t grasp the idea of negative painting.

In the words of my trusted YouTube instructor, Matthew White explains,

Instead of painting the object… you are painting the shapes around the object.

What!?

See for yourself.

In other words, negative painting is “reverse painting” i.e., painting around the area you want to have an effect on.

I don’t know about you, but this lesson alone on negative painting, was like voodoo magic to a neophyte like me.

From Planes and Paints to Psychotherapy

Survivorship bias and negative painting are relevant when we want to improve the work that we do.

But it doesn’t seem intuitive at first.

Most of our professional development efforts focuses on the people we are working with, those who are still in our care.

Much less emphasis is placed on those who fall off our radar, those who prematurely dropout from our care and got overlooked.

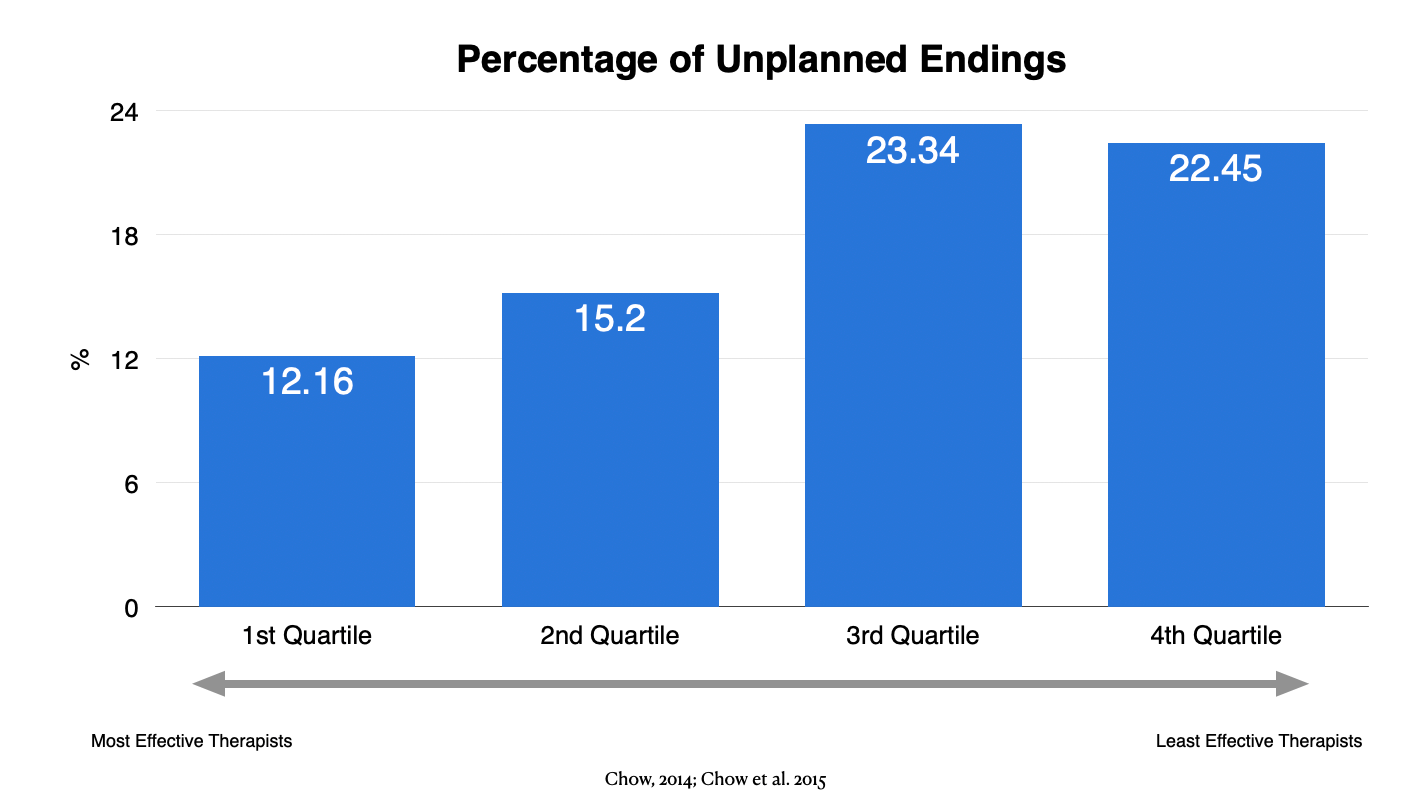

In our study examining the development and practices of therapists, we found that highly effective therapists had fewer unplanned terminations compared with their peers.

RELATED:

In one of my annual reflections, I talked about my clinical mistakes and some of the patterns I uncovered.

In Clearly Clinical Podcast, I talked about why clients ‘ghost’ us.

Final Thoughts

If we focus solely on those present in your caseload and fail to account for those who unexpectedly ended treatment in your care—whatever the reason—we miss a great deal.

Learn not only from those whom you work with, but also those who were overlooked and fell through the cracks.

If this is worth reading, please share this with one of your colleagues.

Notice Board:

Our 3rd Cohort for the Deliberate Practice (DP) Cafe is about the kick-off in Nov 2025. If you are keen to join Scott Miller and I and a small group of like-minded practitioners from all over, join us!

This coming together is much more important than ever before.

Only a few more seats left.

Register now.

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, and the latest book The Field Guide to Better Results. Plus, the new book, Crossing Between Worlds.

You might be interested in my other Substack, Full Circles: Field Notes on the Inner and Outer Life.