Thoughts on Expertise in Psychotherapy. Frontiers Friday #182 ⭕️

From the archive: The Expertise Issue from the Society for the Exploration of Psychotherapy Integration.

This segment is taken from the Society for the Exploration of Psychotherapy Integration (SEPI) newsletter, Vol 4 Issue 2, 2018, The Integrative Therapist.

When I was first asked to response to the Q&A for that issue, I had no idea other giants in the field were contributing too. A handful were people I greatly admired, and devoted hours of my life learning from their body of work.

This included people like Irvin Yalom, David Burns, and Bruce Wampold.

In the future, I hope to do a series of how each of the greats in our field has shaped me.1

For now, here are snippets from each of the them.

Irvin Yalom:

Q. When asked how much therapist’s ability is trainable:

I think it is trainable, but I also think you're off to a head start if you can start off with people who already have this ability.

Carl Rogers at one point said, 'You know, I think therapists probably should be more selected than trained.'

…If I had to select therapists, I would select someone who would really be willing and able to have an intimate relationship with his patient.

Bruce Wampold:

Q. When asked to give his personal definition of what constitutes expertise in psychotherapy:

An expert psychotherapy practice is one that consistently helps clients achieve

their goals. It is really that simple: Expert therapists are those whose clients

consistently benefit from therapy.

Q. What he considered to be the main factors hindering the development of therapeutic expertise over time:

It is very difficult to improve as a therapist. We do our work in private, with little opportunity to practice particular skills. Experts in other fields have coaches, receive detailed feedback about particular components of performance, practice various components outside daily work or performance, and gradually improve.

Unfortunately, given current practices in psychotherapy, it is very difficult to set up conditions to improve but there are agencies and individuals who are using deliberate practice and they are succeeding! Therapists, in the right conditions, do improve their outcomes over time.

David Burns:

Q. When asked how might one go about evaluating expertise:

In my opinion, the only way to assess expertise is by tracking patient progress with brief, highly reliable assessment tests.

Q. What he considered to be the main factors hindering the development of therapeutic expertise over time:

…My research on therapist accuracy indicates that most therapists are highly inaccurate in assessing patients' symptoms, but therapists are not aware of this and wrongly believe they have a reasonable understanding of how their patients feel.

In fact, my research indicates that therapist accuracy in judging depression, anxiety, and anger severity, as well as suicidal urges, is less than 10%.

The same is true of the therapist's perception of empathy and helpfulness (emphasis mine): Their perceptions are very different from the perceptions of their patients. That's why the assessment instruments are, to my way of thinking, absolutely mandatory.

I recommend you read the full issue of The Integrative Therapist by SEPI (click here). Big thanks to the people working behind the scenes at SEPI.

Here’s my response to the Q&A from the old world of 2018. Given the vantage point from 6 years later, I’ve added related links here.

I hope you find this useful.

1. Please give us your personal definition of what constitutes an expert in psychotherapy practice (not as a researcher or academic).

A novice practitioner thinks she's an expert, while an expert practitioner thinks she is a novice.

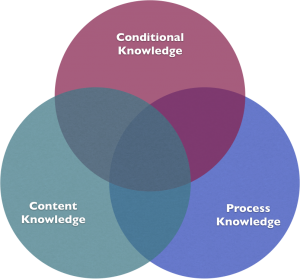

An "expert" in psychotherapy is someone who has deep principles not only of clinical knowledge, but someone who has process knowledge (i.e., the moment-by-moment interaction between client and therapist) and conditional knowledge (i.e., how you would work with someone who is depressed is different if she has a context of bereavement, compared to someone else who has a history of domestic violence).

Our training has been heavy on the clinical knowledge, and light (or absent on the process and conditional knowledge.)

Related Posts:

START HERE: Maps of Knowledge. Frontiers Friday #138.🗺️ ⭕️

If someone needs directions, don't give them a globe. It'll merely waste their time. But if someone needs to understand the way things are, don't give them a map. They don't need directions, they need to see the big picture. ~ Seth Godin. I want to provide you some directions on how you can develop as a psychotherapist.

2. How might we go about evaluating such expertise?

Client outcomes. Not the outcome of one of your clients, but an aggregation of at least 20 cases. I highly recommend a measure that you consistently employ in your clinical practice, preferably one that captures information about the well-being of your client, as opposed to a symptom specific measure. Measure what is of value to your clients, instead of valuing the measures we are told to use.

After all, measurement precedes development. An aside: Measures of adherence and clinical competence rated by experts in specific domains (e.g., CBT), though seemingly intuitive to measure, do not improve client outcomes.2

3. What do you consider to be the main factors hindering the development of therapeutic expertise over time?

Competency.

4. How might therapists counter these hindering factors and reliably grow their therapeutic expertise over time, to the best of their ability?

It's time to stop thinking of psychotherapy as an individual sport. We need coaches to elevate our game.

Despite supervision being the "signature pedagogy" of our field, the traditional approach of clinical supervision is broken. Traditional supervision does not translate to better client outcomes.3 Despite our feelings of "benefit." there are six key reasons why we aren't getting better outcomes from supervision:

1. Theory Talk

Often, the encounter in clinical supervision revolves around case discussion, theoretical formulation, case formulation, and even gossip (isn't that when we talk about someone without him or her present?). This mostly fits under the umbrella

2. Pat on the back

What feels good doesn't necessarily equate to what helps us grow. While it is important to take care of the supervisee's ego, at times we fail to focus on the learner's "growth edge", that is, tending to the supervisee's sense of self as a helper, and helping them stretch ever so slightly beyond that comfort zone.

3. The Lack of Monitoring Progress

You and I are an optimistic bunch. In the absence of real-time monitoring of outcomes and engagement, session-by-session, we fail to detect deterioration and lack of progress. Our self-assessments do not seem to correlate with client outcomes.4

Even when we do use routine outcome monitoring devices, like the Outcome Rating Scale (ORS) & Session Rating Scale (SRS), Outcome Questionnaire (0Q-45), or Clinical Outcome Routine Evaluation-Outcome Measure (CORE-OM), we fail to integrate this in the supervisory process in a meaningful fashion.

I once had a supervisee who insisted on his shortfall in helping a particular client. He didn't have his ORS/SRS graph

at hand. I insisted that he brought it in the following meeting. Here's what the graph says: Outcomes were gradually improving, and alliance had a dip at the 2nd session but continued to pick up thereafter. And here's what the supervisee initially said: The sessions were not helping this client.

We then spent our time working through the supervisee's uncertainty, while holding in mind that the client is likely to be reporting benefit from the engagement. It turned out that the therapist was concerned about answering the referral concern posed by the referring psychiatrist, which wasn't the client's main issue at hand. We proceeded to work out how to focus on helping to the primary client, which is the patient seeking help, and how to address the secondary client, which was the referring psychiatrist.

From the marriage of data and clinical knowledge emerged a type of dialogue that is richer and aids clinical decision making.

4. Not Analyzing "The Game"

Too often, supervisors talk about how to help improve the therapist's skills, without even really knowing how their supervisees work in-session! If Michael Jordan was to work on improving at specific parts of his game, Coach Phil Jackson would not settle for just sitting down and wax lyrical about three-point shots. They would sit down and

scrutinize parts of the video recording of the game. In order for clinical supervisors to have an impact on helping their supervises, they need to know their supervisees actual ways of interacting in-session.

5. The Lack of a Well-Defined Learning Objective

This may be one of the most vital and sorely lacking element in a practitioner's professional development. A well-defined learning objective is key to helping a practitioner stretch and improve. A vast majority of practitioners and supervisors I meet at workshops don't do this. We get lost on HOW to improve, instead of figuring out WHAT to work on that has leverage on actually helping our clients benefit from therapy.

Too often, we engage in clinical supervision on a case-by-case basis, with no coherent thread explicitly weaving in the therapist's learning needs and clinical case concerns. It is vital to help therapists go beyond their zone of proximal development, but to do so, one's current realm of ability and limitations needs to be well-defined. Once this is done, we need to help therapists stretch out of their comfort zone and move into a sweet spot called the learning zone, while making sure that they do not get too overwhelmed and tip over to the panic zone.

Related Post:

6. The Lack of a Tight Feedback Loop

Finally, supervisors often fail to follow-through and find out if what they have discussed in supervision has had animpact on the clients that they have been talking about. Without a tight supervisor-to-supervisee-to-client feedback loop, we are prone to doing the same BS over and over again, thinking that since the supervisee is satisfied with the supervision, it must be helpful.

What we need is a system of learning that actually helps therapists improve, one therapist at a time. Here, the deliberate practice framework5 offers us a guide:

1. Coach: The role of a coach is central to a practitioner's development. She can help create an instructive plan to improve on a specific area of a performance for a well-defined task, and use theother three points below to facilitate growth for the practitioner.

2. Individualized Learning Objectives: I encourage therapists to take the time to identify what to work on before the how. Go beyond case-by-case discussion and see what you need to learn in order to improve your performance. This would include establishing an ongoing learning and development plan in a clinical supervision context and optimizing the use of feedback. Scott Miller and I developed a tool for practitioners and their supervisors to help them in this process: The Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice Activities (TDPA. Update: We have since released an entire edited book based off the TDPA as a springboard, The Field Guide to Better Results . Stay tuned for coming series, as we will release more about the TDPA).

3. Feedback: Without feedback, we would be making up reality. Real-time client feedback helps us to feed forward the therapeutic process. And we need to elicit feedback in a more systematic fashion, as opposed to just asking our clients,"so how's the session for you today?"

Performance feedback needs to be complimented with learning feedback, that is, how you are learning. Learning feedback focuses on the critical learning task at hand, without criticising the learner. Therefore, the delivery of nuanced feedback relies upon the coach or supervisor, to impart descriptive feedback in manageable chunks that encourage clinicians to reach bevond their comfort zone into the learning zone.

4. Successive Refinement: Repetition should not be confused with experience. The mere accumulation of experience does not equate to expertise. Once a learning obiective is clear, it's crucial for a practitioner to make gradual improvements, in the presence of performance and learning feedback. For more, l've spelled out 10 things to avoid in your deliberate practice.

5. How has research (psychotherapy or otherwise) influenced your views on therapeutic expertise and its development? Please provide one or two examples.

Music has been a great force in my life. When I think about psychotherapy, I often draw analogies from music and the other forms of aesthetic arts. For example. instead of trving to think in terms of psychotherapeutic theories. I think more in terms of how to create engagement and impact.

Instead of thinking which model or approach I should use, I would be thinking about how I can create a sense of movement, dynamics and vitality in a session, that facilitates growth and development for each client.

In the development of expertise, we must also learn to hold lightly what we know, to explore what is not yet seen aheadof time i.e., to improvise.6 By improvisation, I do not mean "anything goes." Rather, it means to be willing to create anew experience each time you enter into what the the poet David Whyte calls, "The conversational nature of reality."

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, and the latest book The Field Guide to Better Results.

There are currently 54 articles cued for Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD) at this point; some in “seedling” phase, and others in “budding” phase. If you have topics that you hoped to be addressed—and if you are one of those who read footnotes—I love to hear from you.

Webb, C. A., DeRubeis, R. J., & Barber, J. P. (2010). Therapist adherence/competence and treatment outcome: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 200-211. do:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018912

Watkins, C. E. (2011). Does Psychotherapy Supervision Contribute to Patient Outcomes? Considering Thirty Years of Research The Clinical Supervisor, 30(2), 235-256. do:10.1080/07325223.2011.619417

Walfish, S., McAlister, B., O'Donnell, P., & Lambert, M. J. (2012). An investigation of self-assessment bias in mental health providers. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 639-644.

Chow, D. (2017). The practice and the practical: Pushing your clinical performance to the next level. In D. S. Prescott, C. L. Maeschalck, & S. D. Miller (Eds.), Feedback-informed treatment in clinical practice: Reaching for excellence (pp. 323-355). Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association.

On the topic of improvisation, I highly recommend the following books:Derek Bailey's On Improvisation, Keith Johnstone's Impro, Patricia Madson's Improv Wisdom.

Thanks for the tip!

Interesting read—the knowledge diagram of process, conditional, and content reflected what I had been noticing but hadn’t been able to articulate. In regard to footnote 1: How about a series geared towards new professionals ~ first five years of practice (including pre-licensed)? As someone in this phase of development I’m finding much of your content helpful. I’m curious about how to find a coach and/or mentor?