The 7 Mistakes of Clinical Supervision

“If we cannot show that supervision affects patient outcome, then how can we continue to justify supervision?”

One of the key areas related to our developmental efforts is in the realm of clinical supervision.

Clinical supervision is the signature pedagogy of choice in psychotherapy. I’ve benefited a great deal from the lessons of my supervisors. Some of their words from a decade ago still echo, and have become first principles I keep close in my own work. Most of us regard clinical supervision as integral to our professional development. It’s hard to imagine not having someone to turn to for case consultation and guidance, especially when stuck in a rut and not making expected or desired progress with a particular client.

Given the benefit we often feel from clinical supervision, the logical next question is whether clinical supervision translates into meaningful impact on our client’s well-being.

At least that’s what we would hope for.

Edward Watkins Jr., a researcher from the University of North Texas, conducted a review of 18 empirical studies that examined the impact of supervision on client outcomes. Based on the big picture analysis, Watkins Jr said,

“…the collective data appears to shed little new light on the matter. We do not seem to be able to say anything new now, (as opposed to 30 years ago), that psychotherapy supervision contributes to client outcomes.”

Watkins, 2011, p. 235.

Watkin Jr. made his point clear:

“If we cannot show that supervision affects patient outcome, then how can we continue to justify supervision?”

Eight years later, Watkins published yet another review article called What do clinical supervision research reviews tell us? Surveying the last 25 years(2019). Again, back to Watkins Jr:

Supervision, found to be positively associated with job satisfaction, job retention and ability to manage workload appears to be seen as helpful by supervisees and may even benefit their therapeutic competence (e.g. enhanced self-awareness, enhanced sense of self-efficacy).

But supervision’s favorable impact on outcomes is weak at best, yet to be proven.

Furthermore, the client has been, and continues to be, summarily neglected in supervision research: supervision’s impact on client outcome has yet to be proven.

Practising supervisors and supervisees tend to believe in, and have conviction about, the benefits, power and potential of supervision. But belief and conviction do not necessarily translate into empirical reality.” (emphasis mine)Watkins, 2019, p. 13 & p. 16.

Take a moment and let Edward Watkins Jr’s—one of the leading researchers in clinical supervision—words sink in.

I’ve wrote elsewhere about clinical supervision, as well as a 3-part series on Frontiers Friday #30, #31, and #32.

Here’s a summary our my speculations of where we falter.

(Note: The following is an excerpt from the book, Creating Impact).

Here are my seven speculations of why the default approach to clinical supervision has not significantly improved client outcomes (Chow, 2018, 2019a):

Explainoholic

Pat on the back

Lack of Monitoring Client Progress

Lack of Monitoring Engagement Level in Supervision

Not Analysing the Game

Overemphasis on the Self and Neglecting the Impact on Client

Lack of Focus on Therapist’s Learning Objectives.

1. Explainoholic

I am an expert “explainoholic.”

Given my experience at training other therapists and supervisors, I learned that there might be a need to create an “explainoholics anonymous” meeting—and I’m in it too.

The clinical supervision encounter typically revolves around cases discussion, case formulation and theorising about the clinical pathology. This fits under the umbrella of clinical conceptual knowledge, and does not actually delve into moment-by-moment interactional patterns that unfold in a therapy hour. In other words, we often end up waxing lyrical on how a case may be conceptualised in a psychodynamic framework or emotion focused, or from a CBT perspective. We become quite good at developing the skill of a professional explainoholic.

Not only does this disembody the conversational nature of reality in therapy, but we also assume that the key is to obtain a thorough case formulation of the problem at hand. In 1939, a young psychologist aptly pointed out:

“…A full knowledge of psychiatric and psychological information, with a brilliant intellect capable of applying this knowledge, is of itself no guarantee of therapeutic skill.”

This was by none other than Carl Rogers.

In other words, given that we are already two steps removed in supervision—and lost in explainoholism, we end up being even more indirect in our attempts to improve client outcomes in our clinical discussions.

2. Pat on the back

When a supervisee presents a stuck case, I bet you have heard this chant within the walls of supervision “…But your client still came back to see you, right?”

In reality, a small percentage of clients (~10%) account for the largest percentage (~60-70%) of behavioral health care expenditures, showing a continued use of services without successful outcomes (Lambert, 2003). More specifically, the odds of someone improving in your care diminishes if the client hasn’t experienced therapeutic gains early on (Erekson, Clayson, Park, & Tass, 2018).

While it is vital to take care of the supervisee’s sense of self, what feels good doesn’t equate to what helps us grow. About a third of our clients continue therapy without experiencing reliable improvement in their well-being. If we continue to bolster their esteem with praise or consolation without helping them identify their growth edge and improve the outcomes of stuck cases, we are doing our therapists and clients a disservice.

If a pat on the back doesn’t soothe the angst of a therapist with a stuck case, we revert to being explainaholics.

3. Lack of monitoring client progress

We therapists are an optimistic bunch. In the absence of real-time monitoring of outcomes and engagement session by session, we fail to detect deterioration and dropouts. A groundswell of studies now shows that the use of measures such as real-time feedback tools not only reduces deterioration in client well-being by a third, but cuts dropout by half, and as much as doubles the overall effectiveness of therapy (Schuckard, Miller & Hubble, 2017).

Even when we use routine outcome monitoring devices, like the Outcome Rating Scale (ORS) and Session Rating Scale (SRS), Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45), or Clinical Outcome Routine Evaluation- Outcome Measure (CORE-OM), we fail to meaningfully integrate them into the supervisory process. We stick to using the measures as an assessment tool, and not as a conversational tool. We go through the motions of administering measures because we are required to, and it is good practice, but it doesn’t feed into actual improvement in client outcomes or adjustment to our approach to suit client feedback.

4. Lack of monitoring engagement level in supervision

Those of you who are already using routine outcome measures as a source of feedback know that it’s hard for clients to give the therapist feedback. It’s also hard – if not harder – for a supervisee to provide feedback about engagement levels in supervision, especially if the supervisor is a colleague.

The reality is that clinical supervisors have a tough enough job ensuring that their input has a ripple effect not only on the therapist, but also on their clients. Having some type of formal procedure to elicit what’s been working for the learner can help focus. In addition, given that supervisors and supervisees may have overlapping roles or collegial bonds outside of supervision, having a formalised feedback procedure in supervision allows both parties to take a pit stop and address issues in real time—not six months down the road when it’s too late—that might otherwise be brushed aside.

Also, your supervisor may not be familiar with the feedback informed treatment (FIT) approach. They may not have had any training in it or agree with it, and therefore not be helpful with that aspect of supervision.

5. Not analysing the game

In any other domain, such as sport, music, acting or public speaking, if one were to seek a coach’s help, it would be unheard of for the performer not to analyse their performance. Yet, in the field of psychotherapy, we do less examining of moment-by-moment dynamics in the therapy hour, and more theorising (see point #1). Most supervisors do not watch snippets or segments of the video recording highlighting specific areas that the therapist should work on. Many supervisors do not record and review their own work, let alone that of supervisees. It is only when they are required for a student or a registrar program that by the supervisor makes observations. Post-registration, these are often abandoned by both supervisees and supervisors.

As in other professional fields, it’s important to record sessions in order to receive specific feedback about the interaction and direction of therapy rather than feedback about a perceived or reported performance.

Feedback is useful when it’s based on a well-defined objective, observables, or specifics.

6. Overemphasis on self and neglecting the impact on the client

You may not agree, but there is an over-emphasis on the self of the therapist at the expense of impact on the client.

Too much supervisory time is spent on superfluous issues such patting the supervisee on the back (see # 2), and not enough on real-time progress monitoring to guide the conversation (see #3). In other words, at times supervision slips into personal therapy.

7. Lack of focus on therapists’ learning objectives

In my training as a psychotherapist, some guidance from clinical supervisors changed my life, and others I nearly got in trouble with, because of my dissatisfaction with a dogmatic focus on models and not actual translation into client outcomes. I’ve been told before to pick another client to discuss who fitted in with a particular modality of therapy that my supervisor was trying to get me to learn.

Even good supervisors didn’t always provide an individualised professional framework for my learning needs, although it was not their fault, as I didn’t ask for such direction. I was left to figure it out on my own, and, most of the time, supervision was on a case-by-case discussion basis.

Meanwhile, our traditional teachings approach in post-graduate courses and national board-approved supervision programs bark up the wrong tree (Chow, 2017) They are obsessed with standardisation—the way Edward Thorndike took Frederick Taylor’s idea of standardisation to improve productivity in manufacturing industries, which permeated into our factories and education system. The courses and programs push for adherence, competency, and treatment fidelity to specific treatment approaches, none of which improve client outcomes (Miller, Hubble, Chow, Seidal, 2013).

Flip the script in clinical supervision

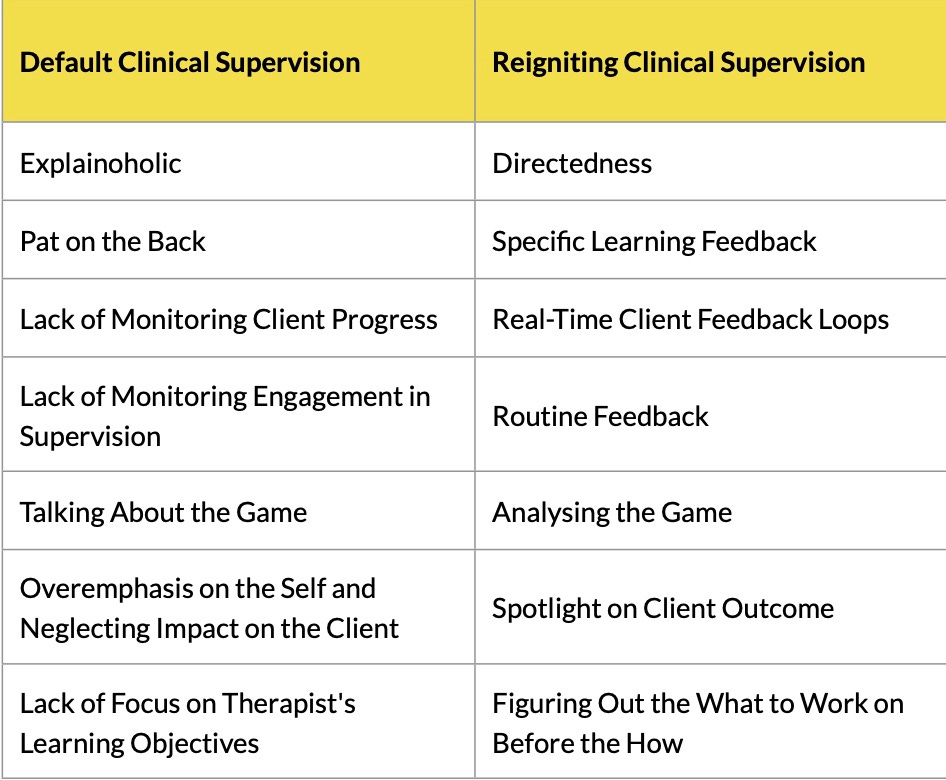

Now that we have gone through the seven pitfalls in clinical supervision, let’s quickly turn things around and find the antidotes.

Table 1. Contrast the Orthodoxy of Clinical Supervision and Reigniting Clinical Supervision

In Creating Impact, I discuss in detail each of the seven antidotes.

Meanwhile, we have to let Edward Watkin Jr’s words echo:

“If we cannot show that supervision affects patient outcome, then how can we continue to justify supervision?”

Reigniting Clinical Supervision Course

I want to take this chance to invite clinical supervisors to join the 13th cohort of Reigniting Clinical Supervision (RCS).

Are you a clinical supervisor?

If so, check out the online course Reigniting Clinical Supervision (RCS) that has been going on for more than 4 years.

Footnotes:

1. Watkins, C. E. (2011). Does Psychotherapy Supervision Contribute to Patient Outcomes? Considering Thirty Years of Research. The Clinical Supervisor, 30(2), 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2011.619417

2. Watkins Jr, C. E. (2020). What do clinical supervision research reviews tell us? Surveying the last 25 years. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 20(2), 190–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12287

3. Chow, D. (2018). Reigniting clinical supervision: Taking clinical supervisors and psychotherapists to the next level of real development (web-based workshop)

4. Chow, D. (2019a). Daryl Chow on Reigniting Clinical Supervision [Interview]. https://www.psychotherapy.net/interview/daryl-chow-reigniting-clinical- supervision#section-cardinal-supervision-mistakes

5. Lambert, M. J., Whipple, J. L., Hawkins, E. J., Vermeersch, D. A., Nielsen, S.

L., & Smart, D. W. (2003). Is It Time for Clinicians to Routinely Track Patient Outcome? A Meta-Analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(3), 288–301. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bpg025

6. Erekson, D. M., Clayson, R., Park, S. Y., & Tass, S. (2018). Therapist effects on early change in psychotherapy in a naturalistic setting. Psychotherapy Research, 14, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2018.1556824

7. Schuckard, E., Miller, S. D., & Hubble, M. A. (2017). Feedback-informed treatment: Historical and empirical foundations. Prescott, David S [Ed];Maeschalck, Cynthia L [Ed]; Miller, Scott D [Ed] (2017) Feedback-Informed Treatment in Clinical Practice: Reaching for Excellence (Pp 13-35) x, 368 Pp Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; US, 13–35

8. Chow, D. (2017b, March 6). Signs that therapists are barking up the wrong tree. Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development. https://darylchow.com/frontiers/ signs-that-therapists-are-barking-up-the-wrong-tree-in-our-professional- development/

9. Miller, S. D., Hubble, M. A., Chow, D. L., & Seidel, J. A. (2013). The outcome of psychotherapy: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Psychotherapy, 50(1), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031097