Measure Growth, Not Competence

Updates by Daryl Chow, MA, Ph.D.(Psych)

View this email in your browser

Measure Growth, Not Competence

By Daryl Chow, MA, PhD on Oct 22, 2019 10:09 pm

The Reimagine Education in Psychotherapy (REP) Series, Part 3.

I cannot fail.

I failed way too many times in my primary, secondary, and even in tertiary education. It was challenging to not be succeeding in a meritocractic, top PISA ranking country like Singapore, the tiniest country in the world with a hunger for big results.

After a 2.5-year hiatus from the education system when I served mandatory National Service, when I finally got enrolled in an undergraduate program, things got serious. The stakes were higher. I’m 21. I’m 3.5 years behind my female friends (time in the army plus one extra year in secondary school for being not so smart).

For the first time in my life, with lots of help from two of my undergrad classmates Joy and Shannen, who were way smarter than I was, I actually did well.

I returned to work as a youth worker, and concurrently do my Masters. It was madness. I juggled work and school and practicum for 2.5 years. No more room for failures. Keep the feet moving.

Even though I was on fire with what I was learning, what’s invisible to others was that I was pushing myself like crazy to make the grade. To get the bloody title of a psychologist. To be deemed by the gatekeepers of my profession that I am competent. There was a chasm.

Education was not the place where I was learning. Education became a stage when I was trying to perform. Learning has left the building.

We Bought This Myth

One of the greatest myth sold is that grades matter.

“Ha,” replied a colleague. “Wait… doesn’t it?”

Many of us would agree that grades doesn’t make you happy in the long-term, in fact, the pursuit of good scores makes you miserable. Neither does it predict future success in your career. Focusing on grades is associated with less risk taking and creativity. But as K. Anders Ericsson once said to me, “measure what people do, not what people say.” Most of us, agree that grades don’t matter, but look at how many of us get caught up with this modern myth in the pursuit of perfect grades. I said grades really didn’t matter to me, but look at what I was doing. I was playing the game. I even played this game a little further when I returned to do a Ph.D.

Grades are a finite game.[1] The rules of the game are defined by the ivory tower of academia. Reach the end of this game, and you get a wildcard. This wildcard lets you decide if you want to play the next game called “the corporate ladder” or, play another round of academia (Masters, doctoral, post-doctoral, become a lecturer).

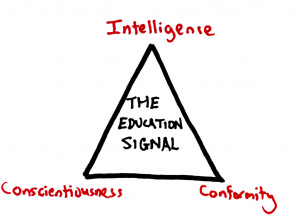

Sure. Grades matter. It sends a powerful signal. It costs a lot to get “educated,” and you are likely to get into a recruitment process for your designated job, as it signals to prospective employer that you meet the trifecta of intelligence, conscientiousness and conformity.[2]

Heck, the alphabets after our names signal not only to the others that we’ve earned this, but it becomes a story we tell ourselves that we’ve made the grade. These post-nominal letters says, “Look, I am competent.”

Working and consulting with therapists from the all over made me realise that so many of us are fearful of committing a blunder, something that signals incompetence. We worry if we aren’t doing “evidenced-based” or evidenced-informed practice, or that we are missing something that the rest of the profession are clued in to, like the latest trauma-focused neuroscience based approach, cutting edge science on self-compassion, or something else.

For some, revealing flaws in clinical supervision, even when we are in training, can be too raw and vulnerable, as we might be judged for being incompetent. That was my experience.

We end up doing our best to perform, to meet some competency checklist pre-defined by the country’s governing body, which paradoxically, impedes our ability to learn.

Not Just Grit

To be clear, I’m not talking about “Grit,” the 12-item scale developed by Angela Duckworth and her team. [3]. Duckworth’s work might have gotten a lot of press, but as the main proponent of grit, she has stated in an op-ed in the New York Times “I worry I’ve contributed, inadvertently, to an idea I vigorously oppose: high-stakes character assessment.” She goes on to say, “my concerns stem from intimate acquaintance with the limitations of the measures themselves… Should we turn measures of character intended for research and self-discovery into high-stakes metrics for accountability? In my view, no.”

Besides, the Grit scale penalises people who “interests change from year to year,” and, “set a goal but later choose to pursue a different one.” In other words, people who change their pursuit are deemed as less gritty. Especially for students in higher education, if we stop and think about it, asking a 18-year-old to stick to their major is like asking him to marry their first sweetheart.

The road of true growth comes with the territory of changing of minds.

(In case you are wondering “what about measuring growth vs fixed mindset?” I’m not referring to that either. Besides, isn’t it a fixed mindset to be asking if a person has a fixed or a growth mindset? For more on this, read this post)

Reimagine This

What if we can fix this? What if we start to truly value growth and not just competence?

I’m not saying we shouldn’t play this finite game of going to higher education. In fact, as a client I would like to see that my therapist is at the very least licensed i.e., competent in the eyes of some pre-ordained registered body that professions pay their annual dues to.

What I’m saying is to change the rules of the game.

What if we figure out a way to measure each learner’s development across time, help them expand their hunger for ongoing development and less about their ability?

Measuring competence triggers an attitude that is limiting, non-expansive, and constraining. We end up doing what I was doing in higher education days, learning for the test. We strive to get from A to Z. In such dogged pursuit, we might end up at the finishing line, but none the wiser. And worse, we become fearful, and as Carol Dweck would say, become fixed in our mindset.

Measuring growth facilitates a climate that values person development. While playing the finite game of academia focusing on growth keeps in mind the infinite game of learning. Here, we aim to get from A to B, then C, and then D, and so on. In a slower pursuit for competence, we end up reaching the finishing line slower than the pursuit of competence, but we end up wiser. And hungrier. And, we grow a little bravely and willing to face our vulnerabilities in the pursuit of learning.

There is now room for failing. Because failing is not equal to failure.

This is beyond quipping about “learning from your mistakes” or about “failing fast.” When we make room for real growth and development, this space allows us to experiment, tinker, and learn. When we focus solely on competence, we rigidify and fail to play the long game of what it means to be a true lifelong learner in the helping profession.

Keys:

1. Measure Outcomes from the Get-Go

It is imperative that we teach therapists to use outcomes and engagement measures beyond just as assessment tools, but as conversational tools.

We need to teach them not to fear integrating such tools into clinical practice—imagine your family physician saying I don’t use the thermometer or the stethoscope because it gets in the way of rapport building with my patients.

We need to guide them on to use measures as a feedback tool, so as to feed-forward and inform the treatment process (see How to Get Better at Eliciting Feedback and How to Get Better at Receiving Feedback). Ultimately, It’s about the use of of clinical data plus our clinical intuition to make better decisions in the practice of psychotherapy.

2. Not “How effective are you?” but “How have you developed?”

If we can teach trainees to integrate measures into clinical practice from the start, we then get to do an important and highly underrated piece in the deliberate practice puzzle: Figure out your baselline.

This is a crucial first step. Figure out where you are before where you need to “grow.”

And here’s the fragile balance. Do not let measures become yet another piece of evaluation, but as a stepping stone to tracking how one is developing across time. Measures can tip a learner into a performance, fixed mindset mode. It is the job of the teachers to facilitate a conducive climate that focuses on growth, not competence. The context determines our mindsets.

So don’t just stop at figuring out “how effective am I?” go one step further and extrapolate “how have I developed” “what have I learned and discovered.” Sometimes, it’s equally important to work out “what’s in the way of my development.”

3. Designing a system of deliberate practice

Renowned decision-making social scientist Herbert Simon said, “The proper study of mankind is the science of design.”[4]

Once we’ve helped trainees use measures as a form of real-time feedback tool, and subsequently helped them establish their baselines, we need to help trainees design a scaffold that supports a system of deliberate practice. To date, the amount of time spent in deliberate practice has been found to be a significant predictor that differentiates the best from the rest. And it’s not just about the amount of time. It’s about how the time is optimised to leverage into impacting client outcomes.

The goal of improving outcomes is not enough. The novices have goals, and the pros have systems. Click here to watch an entire talk on developing a system of practice.

(For more, stay tuned to our forthcoming book with Scott Miller and Mark Hubble, Better Results.)

The Role of Teachers

Based on the foregoing suggestions, there are significant implications for teachers in our field. We need to learn how to interpret and analyse outcome data, and help trainee’s identify each person’s unique growth edge. This is where numbers come to life. No room for the excuse that “I’m not a math person” because this isn’t about numbers. Much like how we use alphabets to tell a story, we need to use numbers in order to leave numbers. These numbers tell an important story. It is the story of how we can help each therapist get better.

As legendary Coach Wooden would say, you haven’t taught until they have learned.

In his book, The Case Against Education, Bryan Caplan poses a question for us to consider to what degree are teachers “sculptors or appraisers”:

By analogy, both sculptors and appraisers have the power to raise the market value of a piece of stone. The sculptor raises the market value of a piece of stone by shaping it. The appraiser raises the market value of a piece of stone by judging it.

Teachers need to ask ourselves, “How much of what we do is sculpting, and how much is appraising?” And if we won’t ask ourselves, our alumni need to ask for us.

Growth is the Measure

Steeped in tradition, the measure of competence served specific functions of filtering and gatekeeping. We need to help students stretch beyond and not worry about making the grade. Climate control, not command and control—or more testing—is needed in institutions of learning, in order to keep the flame of learning alive in the halls of education.

School is not just for school’s sake. School should be designed for the real-world. We can convert the measure of competence to emphasise the measure of growth and development. Going one step further, this should not just be about what’s measured by appraisers of the institution, but by the people who see our help, out there in the real-world.

Measuring growth, not competence is a subtle but distinct shift. Because this would mean that if I were to replay my higher education history, I would fear less about failing, not be plagued by trying to get perfect grades, and have learning be kindled and sustained for a lifetime.

Footnote:

[1] Finite and Infinite Games by James Carse.

[2] A Case Against Education by Bryan Caplan

[3] For more about the 12-item Grit Scale, read Duckworth, A.L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M.D., & Kelly, D.R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 1087-1101.

For a critical review of measurement in education settings, read Duckworth’s and Yeager’s 2015 article.

[4] quote from Herbert Simon, 1988 from p. 82 The Science of Design: Creating the Artificial. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1511391

image by Jonathan Borba. @JonathanBorba

The post Measure Growth, Not Competence appeared first on Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development.

Recent Articles:

Teach the 3 Types of Knowledge and Not Just 1

Kindling the Flame

4 Lessons from 20 Weeks of Very Bad Therapy

“It’s All About the Process…”

Explainaholic