Personal Learnings: Looking Back In Order To Move Forward (Part II of II)

Updates by Daryl Chow, MA, Ph.D.(Psych)

View this email in your browser

Personal Learnings: Looking Back In Order To Move Forward (Part II of II)

By Daryl Chow, MA, PhD on Feb 14, 2019 12:39 pm

“What is essential is invisible to the eye.”

~Fred Rogers

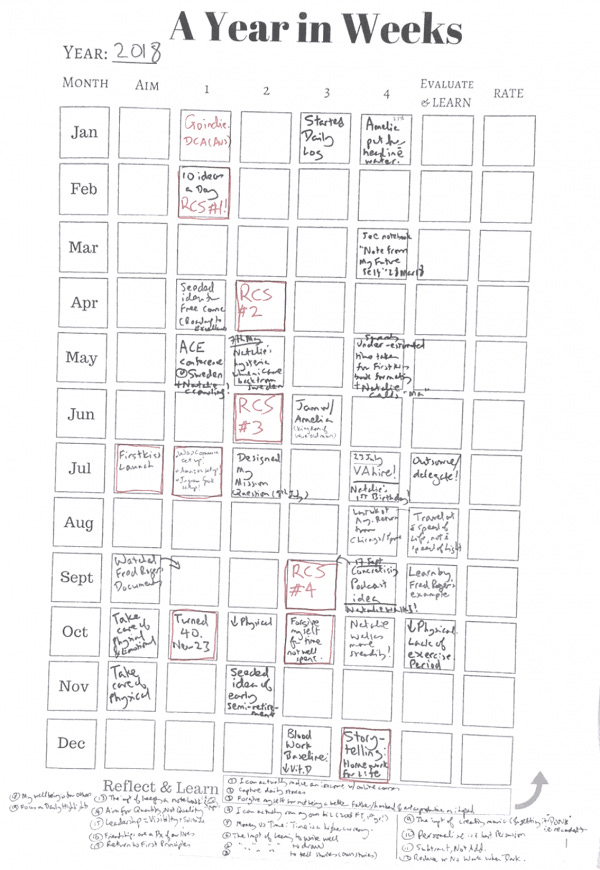

In the last blog post, I wrote about the personal side of I’ve learned from the peaks and troughs of 2018.

Today, I’d share with you 14 embedded ideas I’ve extracted from these experiences from looking back on 2018.

#1. Eliminating the Diffusion of Focus

I can’t trust myself anymore.

A week ago, I’ve pre-decided to ban myself from opening my emailing application. Even though for several months now, I’ve instituted a “no checking inbox” policy in the mornings, I’ve almost every other day, broke my own rule. Heck, they were even justifiable (“What if a client emailed me about my skype id before we connect, or what if there’s a change of schedule?”, etc.). The problem with email is that, as soon as I look for what I’m looking for, I end up being sucked into a vortex of other messages, requests, tasks-yet-to-be-do. It’s a mental drain.

Instead of relying on willpower, I’ve now padlocked myself out of accessing my inbox. I’m using an app called Freedom. I’ve programmed it such that between 11pm to 12pm the next day, I’m unable to open my email application (syncs with my mobile device too).

I don’t know about you, but digital technology has not only sucked away my attention and caused me to have a diffused sense of focus, but it has also robbed me from my intentions. I end up feeling depleted without being as productive as I intended to be. (see points #5 and #11 on how I return to the analog world of writing and drawing in notebooks).

In the past, I see a new application or digital tool, and I think “Ah, that’s going to be useful.” And I end up using it for a little while, and then it just becomes an icon on my desktop or mobile device. Instead, I’m now weeding out stuff, as I try to think less in terms of usefulness of a particular tool (i.e., maximising), but more in terms of autonomy. (i.e, minimising). “Is this tool going to give me more control of my attention? Does this fit with my values and intentions?”

There are its downsides. Just a few days ago, a therapist I was coaching sent me something over email. I couldn’t open the stuff she sent. Our consult was in the morning. I had to explain how my inbox is inaccessible in the mornings. Thank goodness we found a workaround, and she was forgiving of my bizarre behavior.

(Side note: I’m looking forward to Cal Newport’s upcoming book, Digital Minimalism on this topic. I loved his previous book, Deep Work. It’s going to be one of the Top 10 book recommendations that I’m going to share on this blog at a later stage.)

#2. Money vs. Time: Time is the Higher Currency

The beginning of 2018 was the first time I took a deep dive to work 100% on my own. I learned to do almost everything from web design, video/audio recordings, manage my own accounts, etc, but I was confronted with this reality: “Do I really want to trade time for money?”

The short answer is, No, I don’t want to. So I figured, if a task was systematisable, repeatable, and doesn’t need my skillset to get it done, and costs less than what I earn in an hour, I’d trade that by getting someone else to do it. That’s how I ended up contracting a virtual assistant (Big thanks Roxanne!). I’m so pleased that I’m doing that, even though the miserly Chinese in me still feels like I’m wasting money by paying someone on tasks I can do by myself.

What about stuff I can’t do by myself, like copyediting the last book and designing the cover? I ended up outsourcing them to the pros.

#3. Subtract, Not Add

Last year was all about adding projects and stuff that I could be doing. But it only recently hit me that instead of adding, I need to be subtracting. Even though I had plans of reverse scaling my business (I described more about this in part I), so that I can make what I do more personal with the individuals and teams that I work with, I was taking on and adding more stuff to my Trello management board; I felt like I was becoming a hoarder of to-do lists.

I did not know where to begin. I shared this with Eng Chuan, a dear friend that I connect with on a monthly basis as a form of a mastermind group. And he pointed out something so glaring. “How do you recharge?” I said, “I know I need time on my own to think, contemplate, pray, mull, blah blah blah…”

He said, “And when was the last time you had that kind of solitude?”

“Erm, on my last birthday.” (This was more than 3 months ago).

Eng Chuan’s point hit home. It wasn’t about adding another activity in my to-do list. To me, this was about what Friar Richard Rohr calls the spirituality of subtraction. More concretely, I had to remove this “overwrite” that seems to happen every week. Even though I had scheduled Monday mornings for solitude, For an entire year, there was rarely a week that this didn’t get overwritten.

While I continue to contemplate other ways to “minus” stuff out of my life, I think it’s time to remove the “overwrite” button on my days of quiet.

#4. Reduce/Remove Work Time When It’s Dark

Austin Kleon’s blog post sparked this idea. As we are in the thick of a writing project, I broke the bad news with my co-authors that I can no longer connect in my night time. It was taking a toll on me. Thankfully, we found a workaround where we connect in my early mornings, which is their afternoons in the US. (Thanks for your understanding Scott Miller!)

But more generally, attempting to be more in sync and respecting the circadian rhythms makes so much sense. When it gets dark, I now make a conscious attempt to think less about my endless quandaries, stuff like how bad a parent I have been or the size of my bank account.

#5. Keeping a Notebook (and the joys of writing on paper)

This surprised me. I used to keep reams of journals when I was younger. I moved to digital formats in my note taking with no issues. But when I made the conscious choice to return to using a notebook and a pen more than a year ago, I felt back in love with the medium.

I find that at the initial stages of thrashing out ideas, writing on paper is richly rewarding. And I don’t think this is simply a nostalgic throw-back to the good old days of doing things, but I find the process of writing slows me down and allows me to think clearer. Unlike the digital platform where we can muck around with the fonts, format and other fluffs, using a pen and paper helps me to circumvent trying to “get it right.”

I do scan important ideas and notes from meetings with my phone and upload them to evernote, so that I can retrieve them easily when I need it. It seems cumbersome. Some might even say, why not just write on a tablet? True. But I know me. I’m like a squirrel, easily distracted and lured into something else lurking on in my laptop. So the very idea of removing myself away from my computer so that I can think, is strangely, very rewarding.

#6. Aim for Quantity, Not Quality

Since 2014, this is a counterintuitive point that I’ve held close to me whenever I start any project. Aim for quantity, not quality.

Here’s a great story from the book “Art and Fear”:

The ceramics teacher announced on opening day that he was dividing the class into two groups.

All those on the left side of the studio, he said, would be graded solely on the quantity of work they produced, all those on the right solely on its quality.

His procedure was simple: on the final day of class he would bring in his bathroom scales and weigh the work of the “quantity” group: 50 pounds of pots rated an “A”, 40 pounds a “B”, and so on.

Those being graded on “quality”, however, needed to produce only one pot — albeit a perfect one — to get an “A”.

Well, came grading time and a curious fact emerged: the works of highest quality were all produced by the group being graded for quantity.

It seems that while the “quantity” group was busily churning out piles of work—and learning from their mistakes — the “quality” group had sat theorizing about perfection, and in the end had little more to show for their efforts than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay.

The key for me is to depersonalise (not in a clinical sense), suspend premature judgment, and allow myself to get out of the way. This concept is especially useful in the initial stages of creation.

#7. Leadership = Visibility + Solitude

In 2017, an executive at a company I was consulting with said to me, “We need thought leadership. You are one of them.” I thought to myself, “What the heck is ‘thought leadership’?”

I’m still not sure what that meant, but one part of this notion of leadership that resonates for me is to be willing to put stuff out there. I was hugely inspired by reading Austin Kleon’s book, Show Your Work.

For a painful introvert like me, making myself visible in workshops, consults, online courses, and blogging regularly has been a leap. (This is what’s invisible to most people. But inside, I’m like a duck out of water). While it is intentional and essential for me, I’ve come to experience that “visibility” alone without solitude is a slippery slope to be in.

“Almost everything will work again if you unplug it for a few minutes…

including you.”

~ Writer, Anne Lamott, TED talk.

In Lead Yourself First, judge Raymond Kethledge and CEO Michael Erwin define solitude as “a subjective state of mind, in which the mind, isolated from input from other minds, works through a problem on its own.” One of the biggest and most recent challenges I’m faced with is not so much as being alone, but rather, refraining from “inputs”. But as I look back, even beyond 2018, moments of prayer, contemplation and no inputs were not only clarifying, but the experience felt like light doses of nutrients.

I’m returning to solitude on a regular basis (see point #3. Subtract, Not Add. Thanks Eng Chuan).

#8. Focus on Daily Highlights

The more I ask people and the more I look up about this (see Philip Zimbardo’s book, The Time Paradox), as we get older, time seems to speed up.

I learned about creating “daily highlights” from ex-Google employees Jake Knapp and John Zebratsky’s book, Make Time. It’s pretty straightforward but easy to slip by. On a daily basis, I would schedule a period where I would do one “highlight” for the day. This could be sometime that brings joy to me personally, or it could even be sometime I want to get done (like today, my highlight is to complete writing this). Other days, it could be as simple as listening to a song in its entirety without multitasking, reading a book, or watching a movie with the Mrs. when the kids are in bed.

#9. A Serious Re-look at “Parallel vs. Serial” Approach…and Planning Fallacy.

This gets to the heart of a problem I raised in Part I of this blog post, which is, I have “too many planes and too little runway.”

I learned this idea from Jonathan Fields some years ago, and I tried as hard as hell to make this world in 2018; doing one thing at a time in series (one at a time) rather than in parallel (couple of things going on at once). The rule was to Let one thing take flight, before going on to the next project. However, because of my multiple roles, writing projects, clinical duties, research trials, I found this to be nearly impossible.

When I was looking back in 2018 , I realised that the issue wasn’t the principle of “parallel vs serial”, it was that I over-ride whatever I stipulated to do. But digging little deeper, as I review my calendar, this was because, on an almost daily basis, I fall prey to planning fallacy. That is, I jammed too much in on a daily/weekly basis, thinking I can complete a task within an optimistic think frame. (Even while writing this blog post, I thought I would take 2hrs, but it’s taken me 5!)

To help me do one thing at a time, I discovered that the solution is by adopting the following strategies:

1. Create buffer: As mentioned in Part I, for even task, I multiply 1.5 to the budgeted time I give myself. And I try to also create white space in calendars to deal with stuff that crops up (If you open your email, stuff almost always crops up!)

2. Create visible weekly/monthly goals: I use Trello boards to manage my projects. I have a board called “Goals to the Now” which lays out what I need to attend to on a weekly and monthly basis. I also have a list in Trello that parks what’s on for the next week. By reviewing this every Monday morning, and on a need’s basis, I’m able to get a semblance of directionality. For my daily work, I now go by themes. For example, when I’m not traveling, my daily defaults look like this:

Mondays: Visioning and Creating Hats

Tuesdays: Creating Hat

Wednesdays: Consulting/Coaching and Manager Hats

Thursdays and Fridays: Clinical Practice Hat

Weekends: Family Time (funny hats)

#10. Learning to Write

“A professional writer is an amateur who didn’t quit.”

~ Richard Bach

Through the act of writing more in the last few years, I’ve accidentally uncovered something significant: I had so many gaps on what I thought I knew. Even though I might have used those concepts and taught them to others, I soon realised that writing as a way of thinking is a potent form of clarifying my knowledge. Write not what I know, but writing as a way of knowing.

I also found myself confronted with a sheer lack of control and understanding of grammatical rules. I ended up reading books on writing (Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott, Grammatically Correct by Anne Stilman, Writing Tools by Roy Peter Clark), while carefully navigating not falling into the trappings of reading about writing as an escape from actual writing.

I highly recommend for therapists to write. They can do this by capturing their weekly learnings. In brief, weekly learnings is simply a form of bite-sized structured journaling. First, you look back at your week on a Friday, and recall all the clients that you’ve seen. Second, you note down ONE key learning from those encounters. This could be something that went well and worth noting. The other could be an error or mistake that occurred. The final step is to extract a guiding principle from that specific example.

Here’s a recent example. I was working with Roger and we were five sessions in tackling his experience of anxiety and periods of severe low moods. We made some initial gains regarding dealing with his work life, but we started to go in circles. We made specific plans on what he could work on in between our meetings. However, whenever he came into sessions, he would immediately jump in and say, “I didn’t do the homework.” I said to him that I was less concerned about the “homework” as I was more concerned if he was getting better. Roger said, “Yeah, I know… I know these stuff, but I can’t seem to make myself do what I know is right for me…” And then he would go on to talk about the situation he was in.

So I said to him, “Roger, I’m sure you noticed this pattern in your speech. You say a lot of “Yes, but’s.” (He agreed). “What I want to know is, what is the justification of going through the pain and hassle in making these changes in your life?” We went back and forth. He ended up saying this “For my daughter.” So I said to him, “I’m so glad you said this. I think we need to remember, whatever we do to get yourself out of this mess, to rebuild your life, is ultimately, less about you, and more for your daughter.”

The guiding principle I extracted from this example was “Get to the Why Before the How.” I realised I was harping too much on helping him with the “how” and failed to see that I have yet to help him ignite the deep and visceral reason that would propel him.

#11. Learning to Draw

Another area I got obsessed in 2017-2018 was learning to draw. Not drawing portraits or still-life, but like drawing stick figures, diagrams, symbols, so as to quickly convey an idea.

I’ve found this to be a powerful skill to improve. Not only my notetaking has become more vivid in my memory due to drawing my ideas out, but also in communication an idea in teaching.

If you are looking to improve your ability to draw and communicate ideas, I recommend Dan Roam’s At the Back of a Napkin, and Graham Shaw’s The Art of Business Communication.

I’m still not there yet, but I love the process of drawing and seeing an idea come to life in a visual. (This is something Scott Miller, Mark Hubble and I are currently attempting to do in our new book).

#12. Learning to tell Stories

So many things to learn right? I’m very much a non-linear learner. I find jumping from one topic to another rewarding. This messy process allows me to cross-pollinate ideas from divergent worlds.

Sometime in mid-2018, I wanted to improve on skills that can be not only be cross-wired into my different roles at work, but also has leverage. So I figured I should learn to improve on 1. Writing, 2. Drawing, and 3. Storytelling.

Two books that really helped me with storytelling learning project was The Story Factor by Annette Simmons, and Storyworthy by Matthew Dicks.

Watch 36-time Moth StorySLAM champion & 5-time Grandslam champion Matthew Dicks performing his craft of storytelling:

Seems pretty straightforward, isn’t it? Like the craft of psychotherapy, so much goes into what Dick does in shaping his stories, which is often invisible to the naked eye (increasing the stakes, 5-sec moment of change, creating surprise through contrast… just to name a few!).

#13. Capturing Daily Stories

As you can tell, I was totally inspired by storyteller Matthew Dicks new book, Storyworthy. I took his idea about “Homework for Life” (he explains this in this other video), and baked it into my daily routine.

So every night, after bedtime reading with my 5 yr old, I look back at the day’s event, and I try to capture memorable moments. Like Dick’s advice, I limit the number of words to a few sentences, so that this would become doable in the long-term, and not just get a spike of activity at the onset. Similar to my routine of capturing weekly learnings, this practice sits well with me. For sure, there were days when I let this slip. But the benefits I’ve experienced far outweighs the hassle:.

a) I get to capture memorable thin-sliced events with my kids;

b) This Daily Stories journaling triggered memories of past events that I get to pen it down, and

c) I’d get a store-house of personal stories that I can share in my teachings and even in therapy when it calls for it.

Even though I’ve logged 46 entries for the “daily stories” journaling to date, the biggest plus is that I’m becoming more intentional with my days.

Thanks Mr. Dicks.

“We do not remember days, we remember moments.”

~ Cesare Pavese

#14. Return to First Principles

This point is somewhat a meta-principle. Studies show the differences between an “example learner” and a “rule learner.” [1]. Example learners memorise one example at a time, whereas rule learners extract the underlying principles or “rules”. By developing an ability to contrast various examples and figuring out its similarities, the learner reaps the payoff of being able to extract the principles and transfer this mental representation—this “chunk”— into other related scenarios. [2].

I found that the distance of looking back and attempting to extract patterns from concrete examples, is highly illuminating. But here’s a warning: We are a pattern-craving species. Our minds are often seeking to not only spot patterns, but also derive meaning, even if it were random.

In his book, Mindware, social psychologist Richard Nisbett says,

“Simply put, we see patterns in the world where there are none because we don’t understand just how un-random-looking random sequences can be. We suspect the dice roller of cheating because he gets three 7s in a row. In fact, three 7s are precisely as likely as 3, 7, 4 or 2, 8, 6. We hail a friend as a stock guru because all four of the stocks he bought last year did better than the market as a whole. But four hits is no less likely to happen by chance than two hits and two misses or three hits and one miss. So it’s premature to hand over your portfolio to your friend.”

Boiling it down to first principles require more deliberation. But, the rewards are worth it.. Here are some of my related posts on first principles:

Develop First Principles Before The Methods

Three Ways to Develop First Principles in Your Clinical Practice

First Principles: The 5-Step Process for Deep and Accelerated Learning in Therapy

~~~

We started off this piece with Fred Rogers words that he has on a plaque in his office, “What is essential is invisible to the eye.” Keep his words close to you.

My attempts in writing about these ideas that I’ve extracted from the bliss and blisters of 2018 is to make visible what is essential for me that was going on behind the scenes. In a leap of faith, I operate from this assumption that “I = WE“.

Make time to consider what is essential for you.

~~~

Notes:

[1] Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. London, England: Harvard University Press

[2] McDaniel, M. A., Cahill, M. J., Robbins, M., & Wiener, C. (2014). Individual differences in learning and transfer: Stable tendencies for learning exemplars versus abstracting rules. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(2), 668-693. doi:10.1037/a0032963; Gick, M. L., & Holyoak, K. J. (1983). Schema induction and analogical transfer. Cognitive Psychology, 15(1), 1-38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(83)90002-6

The post Personal Learnings: Looking Back In Order To Move Forward (Part II of II) appeared first on Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development.

Recent Articles:

Private Thoughts: Looking Back In Order to Move Forward (Part I of II)

What It Means to Be At The Frontier

What Does General Athleticism Got to Do With Psychotherapeutic Skills?

Instead of The “10,000” Hour Rule, Why Not The “60” Hour Rule?

How Do You Grow as a Clinical Supervisor?