Does Your Mindset Really Matter?

Updates by Daryl Chow, MA, Ph.D.(Psych)

View this email in your browser

Does Your Mindset Really Matter?

By Daryl Chow, MA, PhD on Dec 15, 2017 11:06 pm

Photo by Vincent van Zalinge

Over the last few decades, much research has been published based on Carol Dweck’s idea of Mindset,as summarised in her book, Mindset: A New Psychology of Success, which mainly contrasts fixed mindset (“You have a certain amount of intelligence, and you can’t really do much to change it.”) and a growth mindset (“I believe my intelligence can be developed”).

Take for instance, In a longitudinal study with 7th graders, Blackwell and colleagues (2007) found that those who believed that their intelligence is malleable (growth mindset) were more likely to improve their mathematic grades over the course of two years. Conversely, those who believed that their intelligence is fixed (fixed mindset), flat-lined in their trajectory of improvement in their mathematic grades.

That’s an impressive finding.

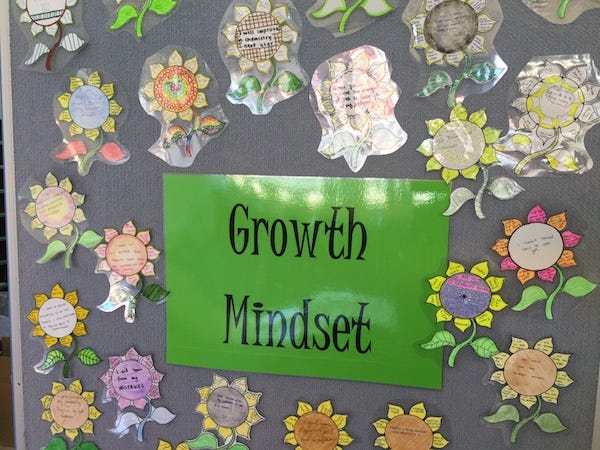

In The Classrooms

Here’s some pictures I took in a high school classroom that “impressed” me even further:

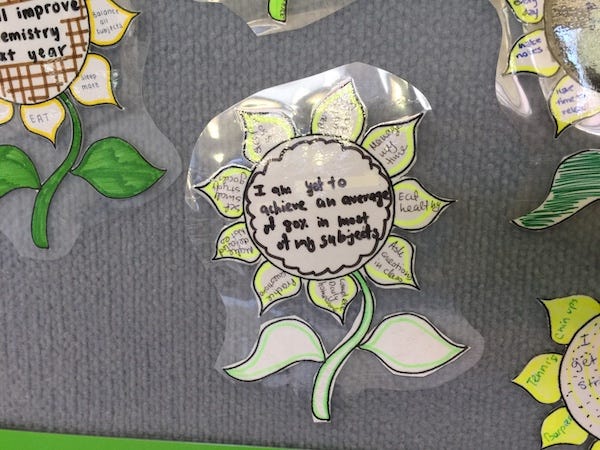

Take a look at some of the specific writings under the “Growth Mindset” categories from high schoolers:

I don’t know about you, but moving to Waiheke Island isn’t such a bad goal to have! (Wait, how does a teenager actually save $1000 in a month?). If these pinups are representative of what’s being taught in schools about fixed vs growth mindsets, I worry that we’ve lost the plot.

~~~

Here’s a useful graphic from the brain pickings website by Maria Popova on the fixed vs growth mindsets:

Of Two Minds

With all the past research in mind regarding fixed entity of ability (fixed) vs incremental theory of ability (growth) mindsets, we set out to test this idea with therapists. As part of a series of hypotheses we were investigating with a bunch of therapists in the UK within our initial Supershrinks Study[2]. We asked the following question:

To what extent does differing mindsets (I.e., Fixed vs Growth Mindsets) of therapists, predict differences in client outcomes?

Though our initial research highlighted the impact of deliberate practice [2] on therapist performance, what we didn’t find in our initial Supershrinks study is equally important. To our surprise, therapists’ mindsets didn’t matter. Their mindsets did not predict their performance.

How can this be?

I had my suspicions, as this flew in the face of the existing evidence out there. (It was also at this time I was reading about the replication crisis in social sciences and the medical profession, which has gotten me worried.)

I began to wonder: Maybe I made a mistake…Maybe because our dataset is small…Maybe it’s not what people say they believe, but what they do that counts.

Does Your Belief About Yourself Matter?

Another piece of the puzzle came in from the same Supershrinks study: Therapists who reported to have higher healing involvement (HI)—that is, feeling motivated, affirming, experiencing states of flow in therapy and efficacious—predicted POORER outcomes than their colleagues who rated themselves lower in HI.[3]

Again, this is counterintuitive of David Orlinksky and Michael Ronnestad found in their international study of thousands of psychotherapists who endorsed healing involvement to be really important [4]. Perhaps it’s true that the novices thinks like they are experts, while the true experts think like they are novices.

Once again, Maybe it’s not what people say they believe, but what they do that counts.

~~~

The False “Growth Mindset”

I couldn’t be more relieved when I read educator and writer Alfie Kohn’s post in Aug 2015 “The Perils of ‘Growth Mindset’ Education,” Kohn points out a central problem with this whole “growth mindset” enterprise.

Kohn says, “The problem with sweeping, generic claims about the power of attitudes or beliefs isn’t just a risk of overstating the benefits but also a tendency to divert attention from the nature of the tasks themselves…But the first problem with this seductively simple script change is that praising children for their effort carries problems of its own, as several studies have confirmed: It can communicate that they’re really not very capable and therefore unlikely to succeed at future tasks. (“If you’re complimenting me just for trying hard, I must really be a loser.”)

The more serious concern, however, is that what’s really problematic is praise itself. It’s a verbal reward, an extrinsic inducement, and, like other rewards, is often construed by the recipient as manipulation.”

More recently, Carol Dweck herself has stepped up, calling a big timeout to this “Growth mindset”. Dweck recently commended about educators efforts in promoting a consolatory “growth mindset”, running with the following equation: Growth mindset = Effort. Dweck points out, “Too often nowadays, praise is given to students who are putting forth effort, but not learning, in order to make them feel good in the moment: “Great effort! You tried your best!” It’s good that the students tried, but it’s not good that they’re not learning. The growth-mindset approach helps children feel good in the short and long terms, by helping them thrive on challenges and setbacks on their way to learning. When they’re stuck, teachers can appreciate their work so far, but add: “Let’s talk about what you’ve tried, and what you can try next.”

Let’s unpack what’s been discussed, and distill two key implications for you as therapists:

1. Focus on the Learning, and not just the performance

Bjork and Bjork (2011) differentiates between focusing on learning and focusing on performing [5] . They highlight that a focus on performing a job may not necessarily translate to an increase in learning. Likewise, a focus on learning may not improve performance in the short-term. Nonetheless, giving attention to promoting learning may improve performance in the long-term. Using current performance as a measure of learning is susceptible to mis-assessing whether learning has or has not occurred

2. Develop and define a clear learning objective that is suited for your professional developmental phase.

Without taking the time to figure out What to improve before the How to improve can easily mislead you into thinking that you are developing. Also, what you decide to work on must have a predictive value of paying dividends to improving your client outcomes. Too often, we end up working on specific paradigms/methods/models that does not account for much in translating into better results.

Once a clear learning objective in defined, this is in turn, fuels and directs the learning process.

~~~

“Great Effort, Son! It’s So Close.”

Some months back, I was shooting hoops with a youth during an outreach session. A kid, maybe 10 or 11 years old, joined us at the court. His mom was sitting at the stands, watching him play. The boy takes a free throw. The ball barely scratches the tip of the rim. It’s as close as to an airball as you can get. His mom says, “Great effort, son! It’s so close.”

My client looked at me with a bewildered grin. Who could fault the mother? She was being so supportive. After all, she was doing what educators are teaching kids these days. Praise the effort, not the outcome, correct?

We should not try to help individuals push for “growth mindsets” (that’s a fixed mindset goal). Instead of assessing, “Does this person have a fixed or growth mindset?” We need to be asking, “How can we cultivate an environment that fosters growth, that specifically helps a learner experience significant moments of learning?”

Questions define the path that we take. Let’s ask ourselves better questions.

Til then.

p/s: I hope you are getting some time for a break during this holiday season!

Daryl

Footnotes:

[1] Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit Theories of Intelligence Predict Achievement Across an Adolescent Transition: A Longitudinal Study and an Intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246-263. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00995.x

[2] Chow, D. (2014). The study of supershrinks: Development and deliberate practices of highly effective psychotherapists. (PhD), Curtin University, Australia.

Chow, D., Miller, S. D., Seidel, J. A., Kane, R. T., Thornton, J., & Andrews, W. P. (2015). The role of deliberate practice in the development of highly effective psychotherapists. Psychotherapy, 52(3), 337-345. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pst0000015

[3] This lends some support to Najavits and Strupps (1994) findings about effective therapists being more self-critical than other therapists, and Nissen-Lie’s (2010) findings on professional self-doubt predicting better outcomes.

[4] Orlinsky, D. E., & Ronnestad, M. H. (2005). How psychotherapists develop: A study of therapeutic work and professional growth. Washington: American Psychological Association.

[5] Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society (pp. 56-64). New York, NY: Worth Publishers; US.

Recent Articles:

The Biggest Stumbling Block Towards Individualised Professional Development

Do Not Become Attached to The Outcome

The Paradox of Focusing on the Therapist

Repairable Models: It’s Time We Fix This

First Principles: The 5-Step Process for Deep and Accelerated Learning in Therapy