Concept Creep. Frontiers Friday #201 ⭕️

The gradual expansion of the meaning of harm-related concepts

Songs as Lead Indicators of Our Culture

Music historian

argues that music, more so than the visuals art, are the lead indicator of where our culture is heading.Gioia says,

Just look at how the lyrics of the 1920s blues songs anticipated the later sexual revolution (forty years in advance!), or how the lifestyle habits of jazz-obsessed beatniks, embraced by a tiny subculture in the 1950s, set the tone for the youth movement of the late 1960s and 1970s. This sensitivity to new ways of behaving is embedded into the musical arts… We want them to be hypersensitive, attuned to the subtle emotional currents.

… Long before treatises and editorials pick up on the coming changes, they have already been set to music.1

If songs foreshadow where our culture is evolving towards, how does our semantic use in daily conversations reveal where we are heading?

Therapy-Speak and Concept Creep

These days, it’s hard not to notice a trend that psychological concepts, therapy-speak, and diagnostic labelings are laced in our conversations, like “trauma,” “toxic,” “ADHD,” “autism,” “narcissism.”

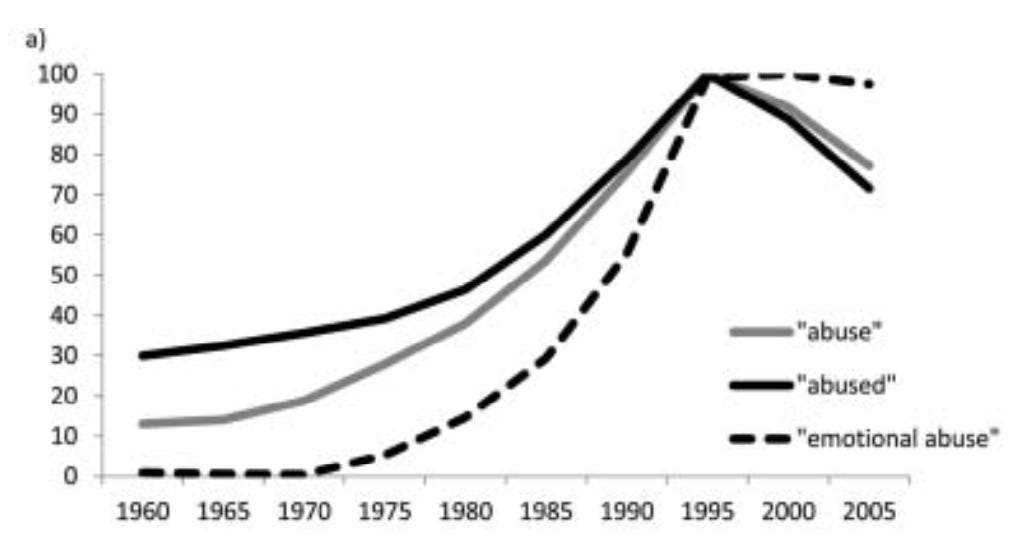

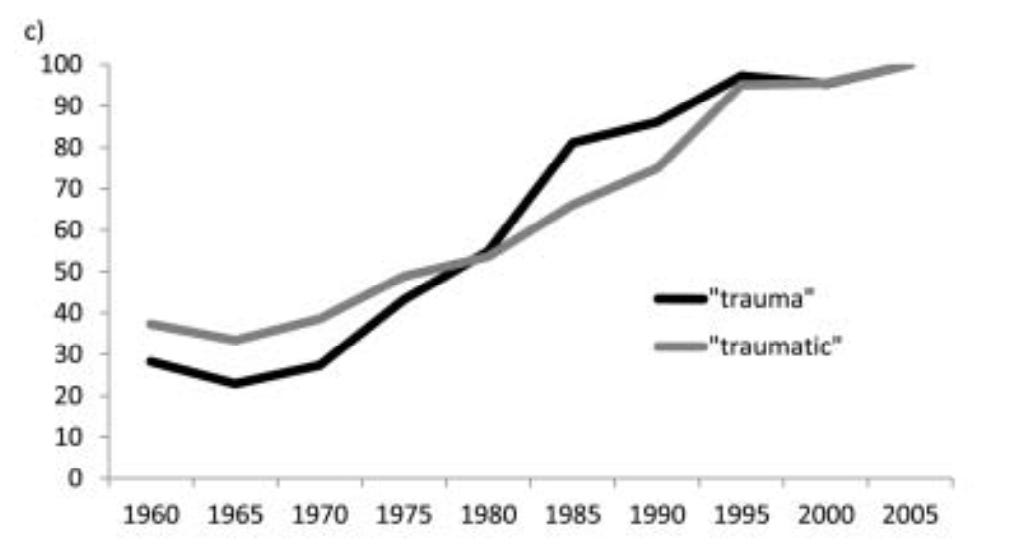

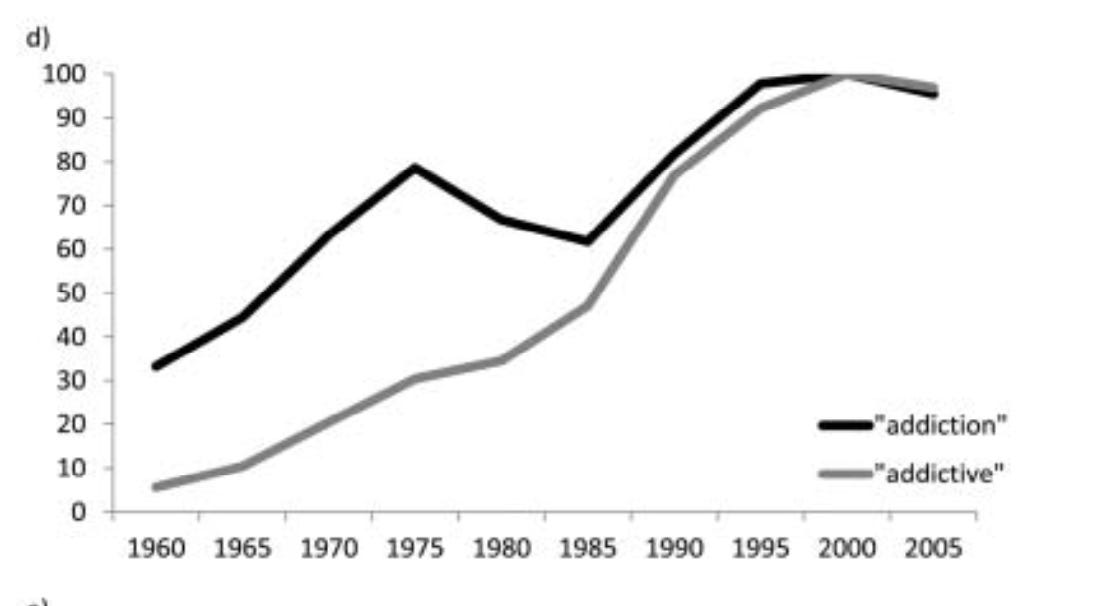

Lets take a look at some specific words and see how they have trended over time:

In his seminal paper Concept Creep: Psychology's Expanding Concepts of Harm and Pathology, Nick Haslam argues that

Concepts that refer to the negative aspects of human experience and behaviour have expanded their meanings so that they now encompass a much broader range of phenomena than before.

Given that we are talking about mental health related concerns more, one can argue that this has led to destigmatisation, thus more help seeking behaviour. In turn, we have also become more empathic and sensitive to suffering and maltreatment.

On the other hand, Haslam points out that the phenomenon of concept creep runs the risk of over-pathologising everyday experiences and encouraging a sense of virtuous but impotent victimhood.

Trauma Creep

Let’s look at a specific example: Trauma.

It was refreshing to hear one of the trauma-informed pioneers Babette Rothschild, who has practiced and written (e.g., The Body Remembers, Revolutionizing Trauma Treatment) on this topic for half a century, on how recent treatment trends might be causing more harm than good.

The full interview is behind a sign-up account. Here are snippets of Babette Rothschild’s interview in the magazine Psychotherapy Networker (Nov/Dec 23)

Rothschild was asked what she taught of the recent rise in trauma awareness:

I think by focusing so much on trauma, we’re lessening the importance of all sorts of other stressful things that happen to people. Judith Herman made it very clear in the ’90s, in her book Trauma and Recovery, that if we call everything trauma, then nothing’s trauma.

Still, you hear people these days saying things like, “Oh my God, selling my house was traumatic. I’ve got PTSD from that horrible real estate agent!”

Even in our field, many people I train or supervise feel that trauma should be our primary focus. When I ask them about client issues that aren’t trauma, they counter with, “My clients only have trauma.” I’ll say, “Well, wait a minute, you mean some clients don’t sometimes just have issues with their job, trouble making decisions at the grocery store, or agreeing with their spouse about childcare?”

Rothschild explains on how people recover from trauma, even without trauma therapy:

Rothschild: In the currently popular focus on techniques, the importance of the therapeutic relationship and other sources of support are often forgotten. The literature is consistent: good contact and support in the wake of trauma is what separates people who experience trauma without long-term consequences from those who go on to develop PTSD. And we know that people can and do recover from trauma without trauma therapy.

Interviewer: How do they recover without therapy?

Rothschild: In the same way humans have for thousands of years: they access and utilise all sorts of resources, including a support network. We as clinicians can get so focused on the trauma and processing the trauma memory, that we forget to help people develop the kind of resources that stabilise their daily life. Sometimes helping people improve their quality of life means processing trauma, but sometimes it doesn’t. [emphasis mine]

People recover all the time from trauma without focusing on what it was that happened, be it recent or long past. Sometimes they recover through spirituality, family, good work, nature, friends, even (and sometimes especially) their pets. Many different things can help.

… Sometimes (therapy) can help, though sometimes it can hurt.

Right now, everybody’s looking for a quick fix or new technique that’s going to cure trauma. But even if an intervention works for one person, nothing helps everybody.

Rothschild went on to state that based on three meta-studies that looked at outcomes for several different trauma therapy methods, “no method stood above any other or helped more than 50 percent of people.”

She’s right. This concurs with the bona-fide trauma treatment and outcome literature. This is also why we recommend clinicians to systematically track outcomes and engagement levels, session-by-session, so that the practitioner can tweak and recalibrate as the therapeutic process unfolds.

What’s “best practice” may not be best for an individual.

If you want to examine this further, here are some interesting reads on the topic of concept creep.

🧐 Research: Concept Creep

This is the original paper by Nick Haslam, 2016. Available in ResearchGate.

Haslam examines the phenomena of concept creep with six illustrations: Abuse, bullying, trauma, mental disorder, addiction, and prejudice.

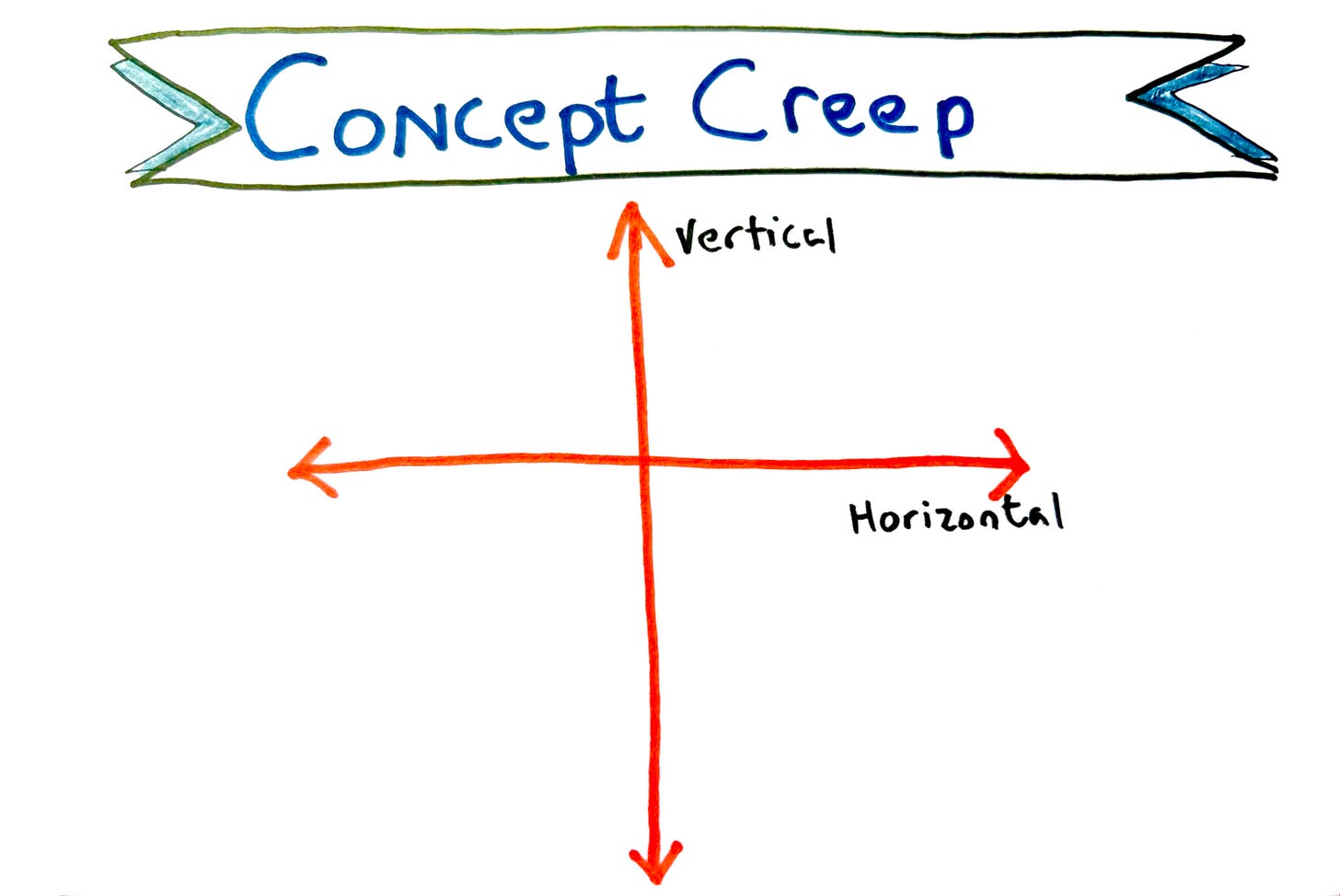

Excerpted from previous post, FF139: ADHD (Part I), there are two types of extension in concept creep:Vertical: increasing inclusion of milder cases

Horizontal: Increasing inclusion of quantitatively different things, which was previously treated as a different semantic description)

At the end of the paper, Haslam elaborates on the implications of concept creep. One of them, interestingly, is a sort of backfire effect.

He says, “Concept creep runs the risk of creating a public impression of psychology as a field that exaggerates misery, inflates mental disorder, excuses misbehavior, and is oversensitive to perceived bias and discrimination.”

👨🏻💻 Web-Read: Gabor Maté Claims Trauma Contributes to Everything From Cancer to ADHD. But What Does the Evidence Say

I’ve read Gabor Maté work in the past, and appreciated his perspective especially in the area of addiction.

However, I couldn’t quite shake off the uneasy feeling of the over-attribution of trauma to everything. I was discussing this with a colleague, and she had the same feeling about this. She sent me this article.

(Hat tip to Siao Geng).👨🏻💻 Web-Read: Mental Health ≠ Wellbeing

Should the concepts of mental health and wellbeing be treat the same?📕 Book: Saving Normal

Former chair of the DSM-IV task force, who became a vocal critic of the diagnostic inflation in psychiatry. His main critique of the DSM-5 was the expansion to the area of normal.

It seems like a distant past when DSM-5 came about. If you are interested to look into this, I’ve saved a 2010 Wired article by Gary Greenberg on this topic: Inside the Battle to Define Mental Illness⏸️ Words Worth Contemplating:

“I’m an introvert, so that’s why I can’t.” No. Definitions are not reasons. [emphasis mine] Definitions are just your old responses to past situations.”

— Derek Sivers, in How to Live, p. 87.

Notice Board

Tomorrow, on 12th of Oct 2024 (Sat), I will be presenting at the Association of Counselling Psychologists (ACP) conference. Two of my lovely ex-teammates will be speaking at this event too.

This is the first time I’m speaking on the pitfalls of deliberate practice: "Seven Ways Deliberate Practice Can Go Wrong.”

If you are in Perth, Australia, it would be such a treat to meet you there!

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, and the latest book The Field Guide to Better Results.

From Music: A Subversive History, pp. 192-193by Ted Gioia

Daryl, I appreciate that you said: “Haslam points out that the phenomenon of concept creep runs the risk of over-pathologising everyday experiences and encouraging a sense of virtuous but impotent victimhood.” Judith Herman's three stages of healing trauma still prevail after more than 5 decades. Babette Rothchild's grounded approach keeps this alive, in the face of concept creep.